|

This lesion is being removed from the distal oesophagus WHAT IS THE LIKELY HISTOLOGY?

a) Hyperplastic polyp

You must be joking!

b) Adenomatous polyp

A gastric adenomatous polyp would surely now be malignant

c) Early malignant polyp

But it's arising from a malignant flat component!!!

d) Advanced gastric cancer

Absolutely!

explanation

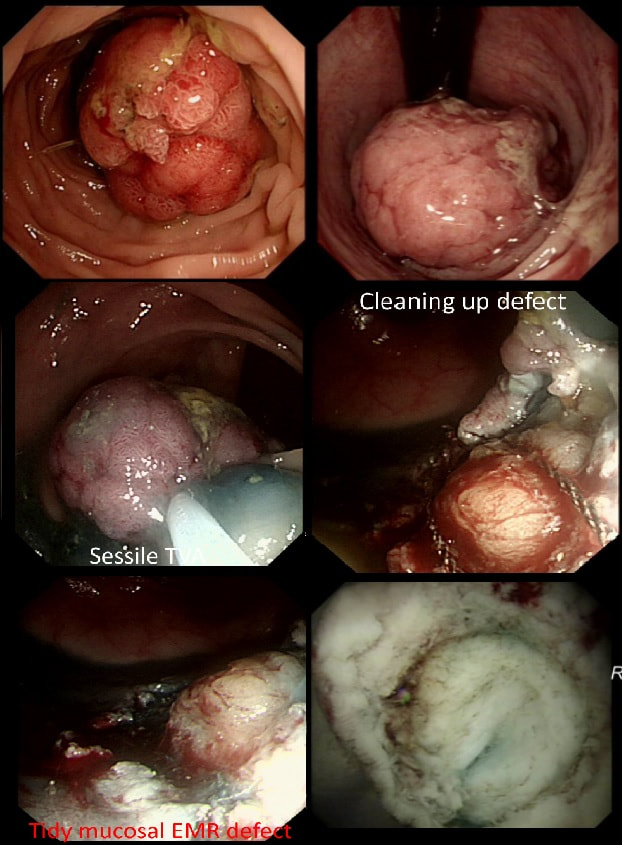

Of course this is all very odd. Clearly this is an advanced cancer at the GOJ. What business do I have in 'attacking' this endoscopically?! Actually, the elderly patient had completed a course of chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for a T2, N0 junctional adenocarcinoma some 30 months previously. Now he has developed dysphagia and a CT confirmed a 2cm polyp at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Histology had shown 'at least IMca' and he was referred for consideration of an endoscopic resection. Clearly this lesion can't be cured endoscopically. In fact, the elderly patient is not a candidate for surgery and therefore there is no cure at all. However, I was thinking that as the cancer is mainly polypoidal, perhaps if the nodule could be removed, his swallowing will improve and he will not need a stent and could be offered brachytherapy. Clearly this was all 'speculative' but I'm glad to say that 6 months later, the patient still has not developed any dysphagia and his now starting brachytherapy. No doubt a better outcome than could be offered by a stent? This is an elderly patient undergoing an OGD because of IDA (iron deficiency anaemia). A lesion catches my eye on the anterior gastric wall WHAT IS THE LIKELY HISTOLOGY?

■ Gastric xanthelasma

The colour is suggestive and gastric atrophy would be the link but it's not quite right...

■ Healed GU scar

But how about that funny crypt pattern?

■ Gastric adenoma

Yes, doesn't this look like a tubular adenoma?

■ Early gastric cancer

Wouldn't the crypt pattern then be very disorganised or perhaps very small?

explanation

The pale colour is odd and reminiscent of gastric xanthelasma which as you know is linked with gastric atrophy which is the likely cause of this patients IDA. However, when I zoom in on the area, the crypt pattern is different here. Of course, this does not fit with a xanthelasma or a scar from a healed gastric ulcer (GU) either for that matter. Interestingly, almost everyone thought that this was an EGC. However, THERE IS a distinct crypt pattern in the centre of the lesion. Furthermore, the lesion isn't red. Remember that cancers encourage the growth of small irregular capillaries which gives them a red colouration. Finally, it doesn't have the typical flat-elevated with a central depression (IIa+IIc) growth morphology. Therefore, your first guess should be a gastric adenoma! This is actually a gastric tubular adenoma which we found in an elderly frail patient with atrophic gastritis some 10 years ago. As she had some comorbidities and it was only harbouring LGD, we decided to keep an eye on the lesion on a yearly basis. The risk of progression is supposedly only 5% with tubular adenomas in the stomach. In contrast, villous adenomas are much more likely to progress (40%). The BSG gastric polyp guidelines have the references if you want to look this up. Of course, the issue is not entirely clear-cut as risk of progression also increases with the size of the lesion (and this is probably 2cm in size) and also with age (patient is now 86 yrs). In some ways, making an initial decision to either 'attack' or 'abort' would be easiest. After all, regular surveillance drains valuable resources and leaves you open to the possibility that at some point in the future, the patient is no longer a candidate for anything more invasive than a haircut but now the lesion under surveillance shows evidence of progression. Then your patient could well ask the legitimate question why you didn't go ahead when he was younger and fit enough but instead wasted his time with pointless surveillance?! My own preferred way to navigate this minefield is to openly discuss the three options with the patient;

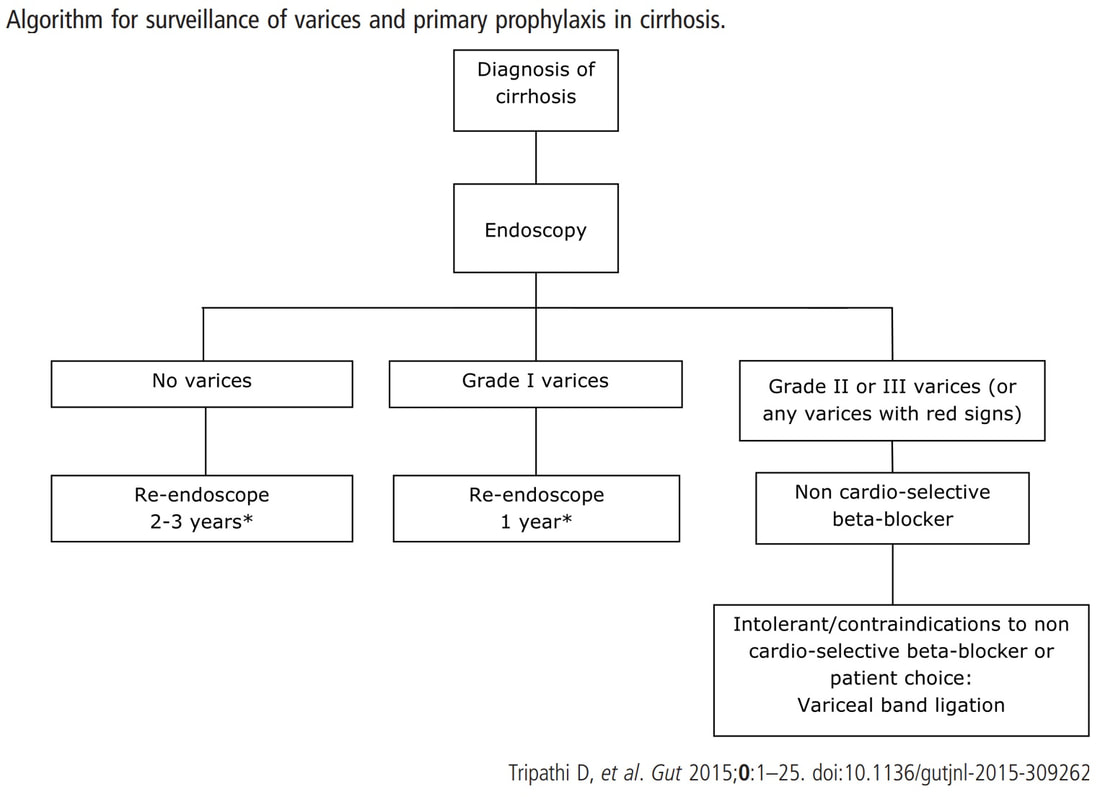

I often wonder if its the personality type which dictates what patients prefer. Perhaps, those who think 'my glass is half empty' usually want to have their lesion resected immediately whilst people who regards their 'glass to be half full', prefer to hope for the best and get on with their lives? This patient is on a surveillance programme due to alcoholic liver disease but has never had a bleed. He is maintained on a non-cardioselective β blocker. WHEN WOULD YOU RECOMMEND THE NEXT SURVEILLANCE EXAMINATION?

■ None, this patient should be offered banding

Correct, if you decide that there are 'red signs' or the varices are grade II or III

■ In 12 months time

Correct, if you decide that there are no 'red signs' and that the varices are grade I

■ In 2-3 years time

Would only be correct if there are no varices at all!

explanation

I must admit that I don't like the current surveillance guidelines for patients with portal hypertension. This is a good example why! Although the LFT's had remained stable and the patient had remained abstinent, you could argue that there are 'red signs'. Of course, the presence of 'red signs' predicts progression of varices [J Hepatol 2003;38:266–72] and because the patient is already on a β-blocker, band ligation should now be started. The truth is that 'red signs' are common and have a poor agreement value between endoscopists.

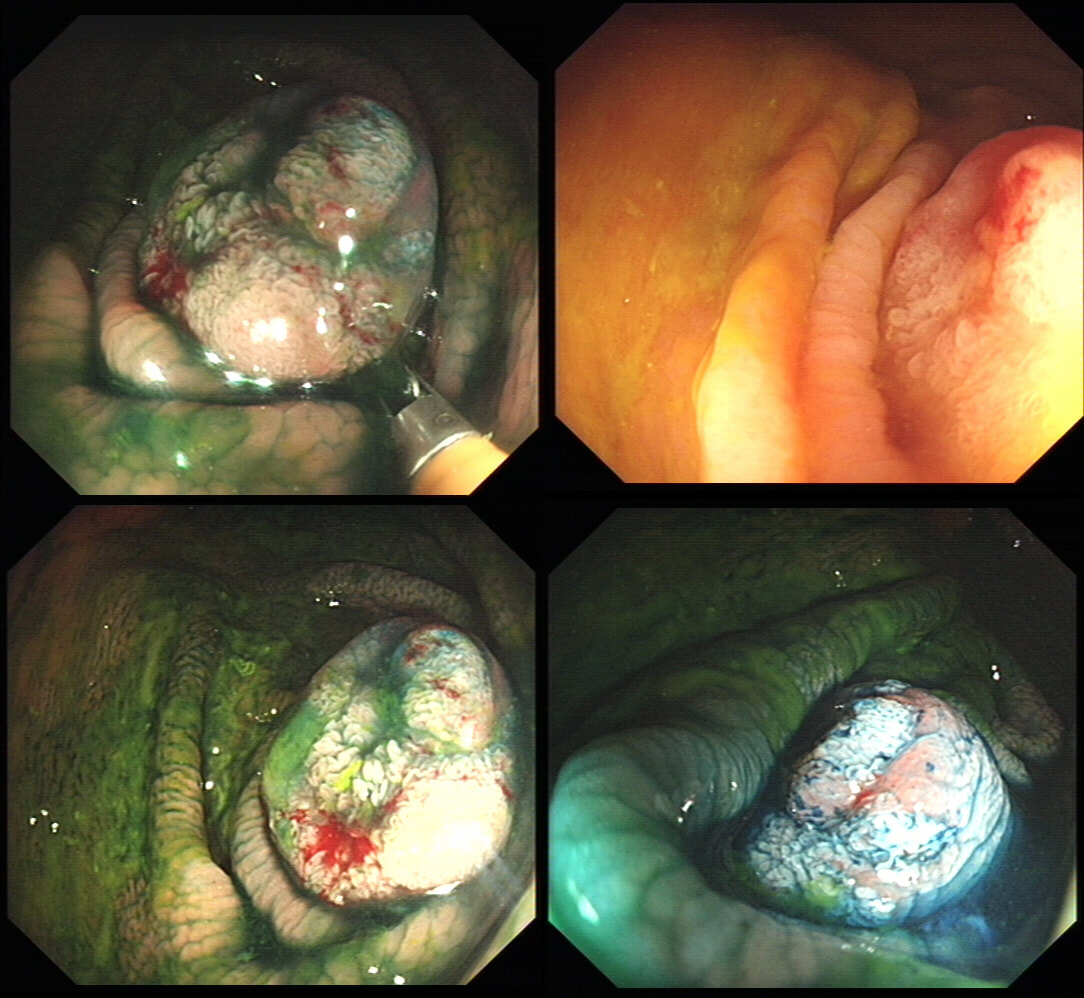

If you decide that there are no 'red signs', and that the varices are grade I only (which depends on the degree of inflation of the oesophagus), the recommendation is to offer surveillance in 1 year. Finally, if you decide that the varices are now grade II (or III), variceal band ligation would be the logical next step. Thus, you can make an subjective argument for any of the above three treatment options. Of course, what you decide will be judged in hindsight. If you decide that these are not red signs and the patient re-presents with a bleed in 6 months time, you could be open to criticism for missing signs of progressive liver disease. Surely, in the modern era of FibroScans, it's possible to predict progression of portal hypertension non-invasively!!! Five years ago, the BAVENO VI workshop only mentioned in passing, that surveillance endoscopies may be avoided in patients with elastography values <20 kPa and a platelet counts >150,000 as these patients are at low risk of progression. Similarly increasing size of the spleen is another warning sign and could be looked for when these patients attend for screening for HCC's. The American guidelines suggest that there is no need to offer patients with untreated viral cirrhosis a screening endoscopy to search for varices IF elastography is <20 kPa and the platelets are >150. They concede that annual elastography and platelet counts may be less predictive in other causes of cirrhosis. However, the American guidelines advice continued surveillance if varices have been found in the past, particularly if liver injury is ongoing. The next Baveno conference in October 2021 will hopefully recommend non-invasive monitoring rather than endoscopy. It would be cheaper, less arduous for patients and offer less subjective findings! The now rather dated BSG guidelines are summarised in the graph below. This subcentimetere polyp was discovered in the rectum of a 60 year old woman undergoing a bowel cancer screening colonoscopy following a positive FIT. Considering the endoscopic appearance and the degree of lifting, WHAT WOULD YOU DO?

■ This is a benign adenoma but it's too close to a large vein for removal

Don't worry about the vein!

■ This is a benign adenoma which I would remove

Doesn't look benign!!

■ This is a likely early cancer which I would remove

Yes it looks evil but should you attack?

■ This is an invasive cancer which I would only sample

Can't argue with that!

explanation

That vein looks intimidating but don't be intimidated! It's not a 'show stopper'. it will move out of the way. However, that polyp does look nasty as there is no definite crypt pattern in the centre, just a swirly surface. However, the lifting is good, suggestive that we stand a good chance of clearing the lesion endoscopically ...

And at this point you can either go ahead and remove the likely early cancer. The advantage is that you get the correct diagnosis whilst biopsies are often inconclusive. The reason why surface biopsies are often unable to confirm invasive cancer is because your pathologists rely on seeing invasion of malignant tissue below the muscular mucosa. The underlying muscularis mucosa is usually NOT included in surface biopsies. However, this is a good example of the potential disadvantages of going ahead to resect the lesion. As you'll see in the video below, I removed it. Histology reported that the lesion was indeed an early rectal carcinoma, 6mm in diameter and with clear margins. However, the deep margin was 'only' clear by 200 microns which of course our pathologists would call a 'positive deep margin'. A 1mm (that is 1000 micron) is the 'accepted' definition of a 'clear surgical margin'. Secondly, there was of course a small focus of LVI. There is usually something to keep you awake at night after removing an early cancer. The disadvantage is obviously that you don't know what to tell the patient!!! - Is my cancer gone or not? - I'm sorry but I'm not sure! - Couldn't you keep a close eye on me with regular colonoscopies and CT's? Well, we could but there is absolutely no evidence that this will save your life IF you still have cancer cells inside of you... Fortunately, there is a study under way in the Netherlands to answer this very question! At the moment, we know that LVI is 'bad' and that the normal next step would be to offer the patient surgery.

These are the NBI images of a young woman complaining of chest pain, dysphagia and reflux symptoms. She also complains of feeling of a 'lump at the back of her throat'.

WHAT WAS THE ORIGINAL DIAGNOSIS?

■ Reflux oesophagitis

Would be an odd pattern surely?

■ Barrett's oesophagus

With squamous mucosa below?

■ Eosinophilic oesophagitis

EoE doesn't look brown on NBI !

■ Oesophageal inlet patch

Yes, but why is it getting smaller?

■ Squamous dysplasia

No dilated IPCL's !!!

explanation

This patient was found to have a large oesophageal inlet patch at the index endoscopy a year ago. Although his symptoms were rather mixed, we have spent 4 sessions on ablating her inlet patch with APC.

Of course, how often you find these will depend on whether you use NBI/FICE/BLE during extubation. Of course you should do because you are then less likely to miss squamous dysplasia! An interesting study reported that gastric inlet patches contained glucagon cells which would normally only be found in the embryo and subsequently disappear. To remind you, the hormone glucagon is normally produced by the alpha cells of the pancreas! Glucagon-like peptide-1 is also secreted by some cells in the ileum and colon. Anyway, the implication is that the gastric inlet mucosa is actually an embryonic left-over. Interestingly, there appears to be a lower prevalence reported in older populations, and some authors suggest that inlet patches may regress with age! Seems odd for a congenital condition? Endoscopic studies have found inlet patches in up to 10% of patients. Whether these give rise to any symptoms is contentious. It has been suggested that inlet patches may give rise to globus sensation due to irritation of the upper oesophageal sphincter by acid or mucus. Furthermore, others have suggested that H. pylori colonization of the heterotopic gastric mucosa causes symptoms. Others believe that it's not just the upper oesophageal sphincter which is abnormal but the entire oesophageal motility may be disorganised in these patients. However, prospective studies have usually not found that patients in whom an inlet patch is found, present with any different symptoms compared to patient without an inlet patch. Of course as anywhere in the body, cancer may develop. A study in Digestive Diseases & Sciences [2018;63(2):452-65] reported on 156,236 gastroscopies and may have found 3 cases of malignant conversion. Assuming that 10% of their patients had an inlet patch, that would suggest that you would have to regularly surveil 500 patients with an inlet patch over many years detect 1 cancer. If you grab 500 random people off a street and scope them annually for 5 years, wouldn't you pick up more than a single early oesophageal cancer? Seems like that lemon is not worth the squeeze? Finally, how about our patient? Over the period of one year, we spent about one hour ablating and completely getting rid of that large inlet patch (well two inlet patches really). The patient reported that symptoms were much better for a couple of months but then returned as before. Of course as she no longer has an inlet patch, we can now conclude that it never did contribute to her symptoms. Must admit that I was sceptical from the start! Show me a prospective RCT with evidence that ablation provides a clinically significant improvement in patients globus symptoms for more than a few months! Until I see that RCT, I will not be offering ablation for these patients.

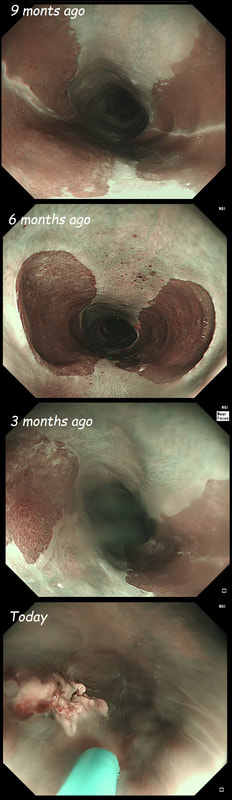

Six months ago a SSL+HGD had been removed from transverse colon. This is the EMR scar.

IS THERE A LOCAL RECURRENCE?

■ No, site looks OK

No it so doesn't !!!

■ Yes, looks like a local recurrence

In fact, it's a malignant local recurrence !

explanation

You will be surprised to hear that samples taken was reported as 'normal mucosa'!!! Fortunately, someone didn't believe this and organised an early follow up for further samples. This confirmed adenocarcinoma with LVI !!!

Bizarre how a lesion can seemingly turn cancerous after resection! Presumably what happened is that it was cancer all along but this wasn't recognised at the 'index histology'. The moral of the story? Don't take the histological diagnosis as the 'bottom line'. These guys are experts but at the mercy of accurate targeting of samples and they only have a few tiny scraps to look at. You on the other hand, can see the whole lesion. If histology, doesn't seem to correspond with your endoscopic resection, more tissue is needed. On the topic of endoscopic assessment, ALWAYS look at lesions in both anteversion and retroversion !

This was found at the caecal pole in an 75 yr old man. Two years ago, a small adenoma had been removed from this spot.

WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT?

■ Ignore the lesion

Perhaps reasonable if patient is unlikely to live more than a few years

■ Keep under surveillance

Reassuring to everyone but may seem ridicilous if patient is turned down for a resection at the age of 80, following 3 heart attacks and a stroke ...

■ Attempt another EMR

Very unlikely to succeed if original resection was done by someone with experience

■ Attempt a full thickness resection

Don't you need further information before deciding?

■ Refer surgically

Uncertain as not studies have compared endoscopic vs surgical approaches

explanation

The crux of the problem is two-fold: First, what is the risk that this lesion will turn cancerous and kill the patient and second what would be the risks of its' removal. • It's a little below 10mm in diameter and according to the data from the NHS BCSP, the risk of cancer within the lesion would be 1.5%. You could perhaps argue that it may be a little greater because it's a local recurrence. On the other hand the surface biopsies had been reassuring only showing a TA+LGD and this probably reduces the risk closer to 1%. The risk of the polyp turning cancerous in the future in the main depends on how long the patient lives. A Norwegian study by Eide T et.al. (Int J Cancer 1986;38;173–6) put the annual conversion rate to cancer for an ‘average’ colonic polyp at 1.25% at 5 years, 2.5% at 10 years and 5% at 20 years. A barium enema study (Stryker S. et.al. Gastroenterology 1987;93:1009–13) of polyps larger than 1cm, estimated the risk of cancer to be 2.5% at 5 years, 8% at 10 yrs and 24% at 20 years. There is also a CTC study of 306 polyps in which only 6% of polyps in 6-9mm range grew larger than 10mm at an average follow up of 2.3 yrs (Pickhart PJ et.al. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):711–20). My own rule of thumb is that if the patient has a life-expectancy below 10 yrs, there may be little to gain by prophylactically removing lesions. This also fits with the latest UK postpolypectomy surveillance guideline which suggest that it should only be offered in patients with life-expectancies greater than 10 yrs (Rutter M et.al. Gut 2020;69:201-23). There are life expectancy calculators available online (just click the link). • As regards 'risks of removal', at one end of the spectrum you have the risks of an 'average colonic polypectomy' (for a subcentimetre polyp. I usually quote a ≤1:200 risk of late bleeding and ≤1:1000 risk of a perforation). Not all polyps are the same and at the other end of the risk spectrum, you have the risk linked with an 'ampullectomy/papillectomy'; 1:10 risk of acute pancreatitis for up to a few months after the procedure, 1:10-20 risk of late bleeding for up to 2 weeks after the procedure, 1:50 risk of a perforation, a 1:10 risk of late stenosis, 1:20 risk of acute cholangitis and a 1:200 risk of death ... • So what can a full thickness resection offer? A recent retrospective review by Ichkhanain Y et.al. from 18 centres (12 in the USA, 5 in Europe and 1 Canadian centre) reported on 66, young fit patients with smallish lesions (avg size 15mm). Surprisingly, 26 of the 66 lesions did not extend deep into the appendix lumen and arguably could have been removed by conventional EMR !? The authors don't elaborate and probably didn't have any further information than that 14/66 lesions had failed a prior attempt at conventional resection. 90% of patients were given prophylactic antibiotics and everyone was admitted after the procedure. Most (70%) of procedures were done under propofol anaesthesia but that is probably the normal approach in the US. The average procedure time was 1 hour. The overall chances of a completely successful endoscopic clearance was 75% (50/66). As regards complications, 17% developed appendicitis (10/58) and 6 pts these patients required surgery. I presume that the appendicitis was rather severe in these cases as patients staid in hospital for an average of 5 days following their surgery! The prophylactic antibiotics did not seem to make any difference to the risk of appendicitis. The success rate of 75% doesn't compare all that well to the reported success rates of ESD which was 95% but that study was small with only 34 cases (Jacob H et.al. Endoscopy 2016; 48: 829-36). • What can your surgeons offer? Insertion of a straight stapling device across the caecal pole whilst pulling on the appendix would probably be a quick surgical procedure without any risk of post procedural appendicitis and a 100% chance of complete clearance. Of course it would be more expensive and the usual hazards associated with a GA and surgery would be in play. By the way, Michael Bourke at Westmead Hospital in Australia writing in Gut 2021;70(2) points out that the surface area of the appendix constitute 7% of the caecal surface area. You will be familiar with a similarly sized triangle of mucosa between the two ends of the ileo-caecal valve and the appendix - the so called 'lawyers triangle' (for obvious reasons)? Michael highlights a study of 34 patients with the 'Serrated Polyposis Syndrome, serrated lesions was found in 23 and some were dysplastic (Pathology 2016;48:30–4). Unfortunately, the single most important fact is missing - what proportion of patients with 'Serrate Polyposis Syndrome' actually develop cancer of the appendix? To summarise, I don't think that it's possible to give a 'correct answer' for this question. The 'correct decision', would depend on the patients life-expectancy, the histology of the polyp (HGD would push you towards resection of course) and whether there is anything to suggest that the patient would not 'do well' if he/she developed severe appendicitis requiring emergency surgery afterwards.

This 3cm polyp was removed from the sigmoid colon. After returning to the recovery area the patient is complaining of severe low abdominal pain.

WHAT WOULD YOU DO NOW?

■ Keep in 'recovery area' for observation

Not 'wrong' a such but you can do more!

■ Bring back into endoscopy room to apply more clips

Now is your chanse to do this before that peritonitis takes hold!

■ Organise a CT

In my experience, it often muddies the water and adds little useful information in this scenario

■ Admit, organise a CT and start AB's

Not 'wrong' but placing clips is more important than any of this

explanation

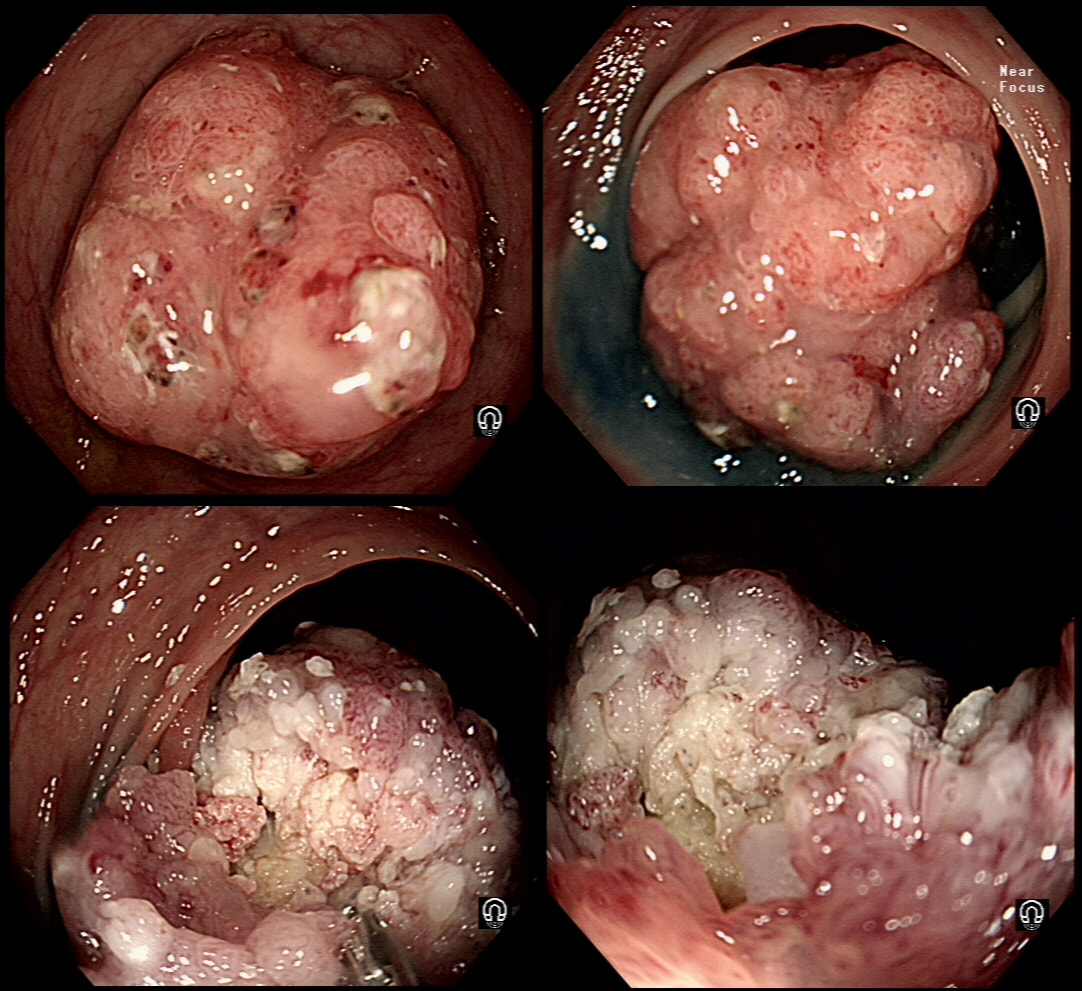

Large sessile colonic polyps are a particular challenge for endoscopists. That surface crypt pattern may not be an accurate reflection of what is hiding inside! When there is cancer hidden at the centre of the polyp, this will induce a fibrotic response (the pathologists call this a 'desmoplastic response') which can tether the polyp to the muscle propria layer. Large polyps being yanked about by peristalsis can also develop fibrosis beneath even if they are benign (example below of an entirely benign VA+TSA harbouring LGD only with dense fibrosis in its centre). Of course, non-lifting is usually obvious when the lesion is small or flat but can be impossible to see below a large sessile polyp.

The first sign that something is amiss is when in spite of 20-30 seconds of yellow pedal power (i.e. a blended cut/coag/pause diathermy cycle), the polyp is still in place! When this happened, I used to curse under my breath, re-set the diathermy and with a strong hand and a further 30 seconds of diathermy, I would usually 'win' the battle and the polyp would fall off. Unfortunately, this would often turn out to be a 'Pyrrhic victory'. There would either be quite alarming bleeding or a perforation. Nowadays, I believe that these large, sessile polyps are best removed by ESD. In a slow, controlled manner you can then dissect below the lesion. If you encounter fibrous tissue you can attempt to dissect around it, abandon or (if you've got the balls) attempt to continue the dissection in the same plane through the fibrous tissue. Of course, you can also deal with those chunky vessels, one-by-one in a more controlled manner. Back to the scenario in question. If I think that there could be any risk that I've perforated, I would bring the patient back into the procedure room to place LOTS OF CLIPS. In truth, I did immediately recognise the peri-colonic fat in the middle image on the right and closed the perforation without delay. That white base to the upturned polyp in the last image, is a sizeable chunk of muscle propria layer. Anyway, provided that there is no peritoneal contamination, the perforation has been thoroughly closed with a virtual 'suture line' of clips and the patient is young and 'sensible', I would observe them for another few hours in recovery and discharge provided that they remain free of abdominal pain. Beware of the patient who remains in pain but claims to be comfortable because he is desperate to get back home... Of course, the patient must understand my verbal and written information that there may have been a small perforation which I have closed with clips but that he/she must return to hospital if further pain develops. Of course, my standard post-resection information leaflet always advice patients to return to hospital if bleeding or pain develops up to 2 weeks after the resection. No antibiotics, no scans, no admission!?! Controversial of course and I must stress that this is my own management strategy. I believe that my way of dealing with micro-perforations is safer than admission (exposing the patient to all the in-hospital hazards of multi-resistant bugs, Covid-19 etc), reduces the risk of 'over-treatment' (CT scans after EMR's or ESDs' always look alarming to the radiologists with gas in the wall of the bowel and the peritoneal cavity which means that surgeons will be reaching for their knives) and cheaper (of course). By the way, I am no great fan of the over-the-scope (OVESCO) clips for three reasons; a) time is of the essence in perforations and with the OVESCO clip you loose time but having to withdraw the scope to attach the device and b) it is very cumbersome and it can be difficult to reach the lesion and c) you only get one chance to get the clip in the correct position. With 'normal clips, it doesn't matter if a clip goes on a little wonkily, you just place another one!

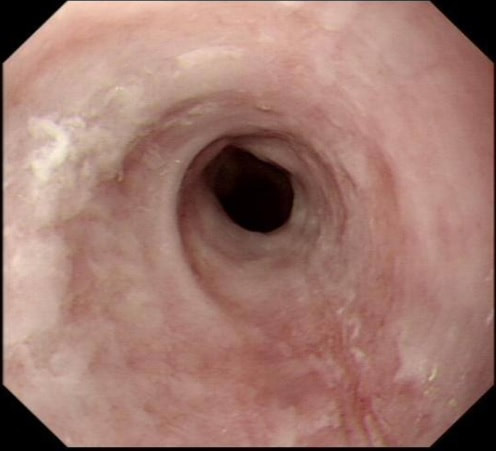

A 16 year old severely handicapped boy is referred for a PEG as he has become increasingly difficult to feed and often vomits after food. Placement of a PEG tube under general anaesthesia is organised. The GA is difficult as the patient is frightened, very strong and with no understanding of what is happening. After a difficult 30 minutes, the patient is asleep and you discover this impassable oesophageal stricture in the distal oesophagus.

WHAT WOULD YOU NOW DO?

■ Abandon the procedure

But the boy wants to eat!

■ Refer for a radiologically placed PEG

But you have found a 'fixable' cause!

■ Dilate stricture and not place a PEG

Yes! Your job is to help him!

■ Reintubate with a slim endoscope and place a PEG

Forget the PEG!

■ Dilate stricture and place PEG

Keep everyone happy? He doesn't need a PEG!

Explanation

This is a recent "real case" of mine!

Endoscopy is unforgiving, a bit like surgery. You have to make the correct decision within a limited time. Tomorrow, OTHERS will be equipped with a "retrospectoscope" which gives them a perfect vantage point from which they can decide if you did "right" or "wrong". In this case, I went ahead and dilated the stricture without placing a PEG. A day later the patient was back eating solid food as normal and the request for a PEG feeding tube was quietly forgotten. Arguably, this was the "wrong" decision and the "correct" thing to do may have been to simply abandon the procedure, send the case back for re-discussion by our Nutritional Multidisciplinary Team, obtain informed consent and then reschedule the procedure in a month time or so. However, the stricture was clearly the cause for the vomiting, sending the patient back with the job unfinished would have delayed the necessary dilatation, put the patient at further risk of aspiration and subjected him to another traumatic general anaesthetic! Arguably the wrong thing to do! But of course, it could have all gone wrong! Oesophageal dilatations are linked with a 1:100 risk of a perforation. Had the family had an opportunity to consider a dilatation? No! Was the patient 'consented' for this? NO! Had you taken samples to ensure that it wasn't a malignant stricture first? NO (but why would a 16 year old have oesophageal cancer?), Therapeutic endoscopy is an odd mix of "thinking on your feet", accepting that sometimes "things go wrong" and working in a team where you can forgive yourself and where others are forgiving when things do go wrong. As a supervisor, sooner or later your trainee will have a serious complication. Surprisingly, we don't recieve any training in handling this! If it's your trainee, bring the conversation somewhere private. Go for a coffee after the list or ward round and hear your trainee tell the story of what happened. Listen and be sympathetic. Usually, I think that this could have happened to anyone. Of course there are things which 'just happen' to anyone. Like perforating an oesophageal dilatation or bleeding at polypectomy. But 'unavoidable mishaps', are more likely to happen to the unskilled trainee or deskilled colleague! When looking into a trainee's complication, I try to consider the following 6 'dimensions':

Actively considering these elements can give you an insight into why it happened. Furthermore, it may provide a clue as to how to help. Should the trainee have fewer cases on the list? Is further supervision required? Finally, supporting your trainee with the coroners report, speaking to relatives and advice on what to expect at the visit to the coroners court is invaluable to the trainee. This is just some of my thoughts to add to your own !

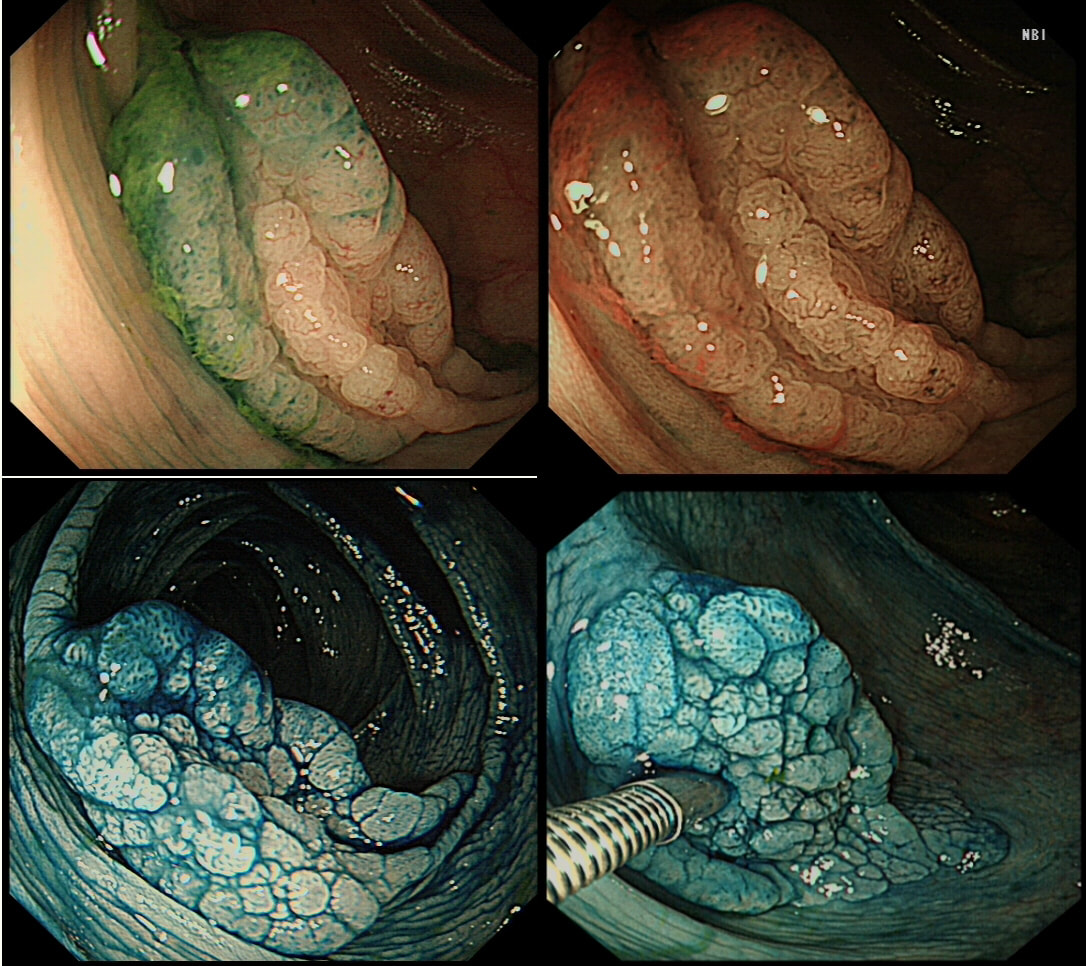

This lesion was found in the ascending colon and was subsequently referred for endoscopic resection.

WHAT IS YOUR ENDOSCOPIC DIAGNOSIS?

SSL

CORRECT!

TUBULAR ADENOMA

INCORRECT!

TUBULO-VILLOUS ADENOMA

INCORRECT!

VILLOUS ADENOMA

INCORRECT!

EXPLANATION

In the indigo carmine dye images, you can see some large, round/oval crypt openings. This was a Sessile Serrated Lesion which actually harboured HGD. 75% of our Facebook group members got the diagnosis right.

The confusing thing is that the growth pattern is that of a LST-G, which of course means that it should be a TVA! I wonder if there is any way I could have predicted the dysplasia? The fact that the lesion is rather "chunky" (but still soft) and not thin and flat, is the sign dysplasia within an SSL . The image caused some controversy back in 2014. Several endoscopists didn't believe that an endoscopic diagnosis could be made. In fact, some hinted that it would be inappropriate to second guess histology. After all, these are the guys with all the answers right? You should stand 'cap in hand' and wait patiently until they tell us what we have seen. It makes my blood boil ! Fortunately, endoscopy has moved on from those dark times. Now we recognise that we have a duty as endoscopists to contribute to the diagnosis. The diagnosis is based on an assessment of the entire lesion and it's degree of lifting. In contrast, our poor pathologists can only give an opinion on the square mm of tissue which we provide them with. That is why they need microscopes! By recognising our responsibility, we accept a duty to develop expertise. Of course, this directly benefits patients as we are more likely than our pathologist to recognise an early malignant polyp and thus target samples to the area which is the most suspicious in appearance. Our pathologists also benefit from our diagnosis, although some endoscopists believe that we shouldn't tell them anything as it could bias their assessment ☺ . To conclude, the combined endoscopic and histological assessment is what is most likely to reach the correct diagnosis - a Team Effort !!! This patient was admitted following drinking caustic soda. This was the oesophageal findings a day after admission. WHICH STATEMENT DO YOU AGREE WITH? a) what was the point of the OGD? b) the appearances indicate a likely good outcome c) the appearances indicate that surgery is likely to be required explanation

Older management algorithms of corrosive ingestion usually involve endoscopy (BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:31). Unfortunately, endoscopy is unable to accurately predict the depth of intramural necrosis (J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:508–522). In fact, CT has been shown to be far more reliable in predicting transmural oesophageal necrosis and identify those patients who require surgery (Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1452–1461). In the largest, prospective study to date, from Paris (Ann Surg 2016;264:107-13) , 120 patients admitted with a corrosive injury underwent both a gastroscopy and CT. Ultimately, 24 patients (20%) required an surgery, 28 patients (23%) developed a stricture and 3 patients died. The authors concluded that 'poor predictors' or signs of more severe corrosive injury and a greater risk of perforation included: burns visible inside the mouth, ↑ serum lactate, alanine ↑ aminotransferase and ↑ bilirubin levels or a ↓ in the platelet count below normal range. Rather as expected, CT was found to be far better than endoscopy in identifying patients with full thickness necrosis of either the oesophagus or the stomach. In fact, there was not one single instance when the endoscopy contributed to the decision making! I do worry about scoping these patients, particularly in the early stages because if they 'perforate', you may be open to the accusation, that you actually 'caused' the perforation. You can imagine the scenario. A precious daughter undergoes an emergency gastroscopy following which things take a turn for the worse. Would it be surprising if the family start suspecting that the endoscopy may have had something to do with the deterioration ? Of course, accidental ingestion of corrosives is common problem in children. In children, it has been estimated that between 7% and 20% develop oesophageal strictures after corrosive ingestion (J Laryngol Otol 1996; 110:1041–5). This figure is lower than for adults, perhaps because children will end up swallowing less corrosive than adults. Unfortunately, in both children and adults, the strictures are often multiple and are usually very fibrous requiring multiple dilatations. An UK regional audit reported an overall perforation rate of 2.6% for oesophageal dilatation with a mortality of 1% . The risk of perforation was lower when dilating benign strictures (1.1% with a mortality of 0.5%) than malignant strictures (6.4% with a mortality of 2.3%) or achalasia (usually 3–4% with a mortality rate <1%). Oesophageal dilatation is most risky in the elderly with reduced tissue strength or when the endoscopist is inexperienced and when strictures are complex, particularly when using weighted bougies blindly (Gastrointest Endosc 2000;51:460–462). In most cases (85–93%) of peptic oesophageal, dilatation gives good symptom relief. However, when dilatations fail, recurrent strictures may be treated with triamcinolone injection (Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41:596–598). Most trials have been carried out using a standard sclerotherapy needle and injecting the stricture with four 1-mL aliquots of 10 mg/mL triamcinolone in a four-quadrant pattern, for a total of 40 mg. For strictures which recur in spite of local steroids, temporary stenting using removable oesophageal stents is an alternative treatment strategy. So, which answer is correct? I would say, A ! At the time, I couldn't see the sense in scoping the patient. Indeed, this turned out to be the case! My endoscopy didn't affect management in any way. The patient was discharged a week later for psychiatric follow up only. |

Categories

All

|