|

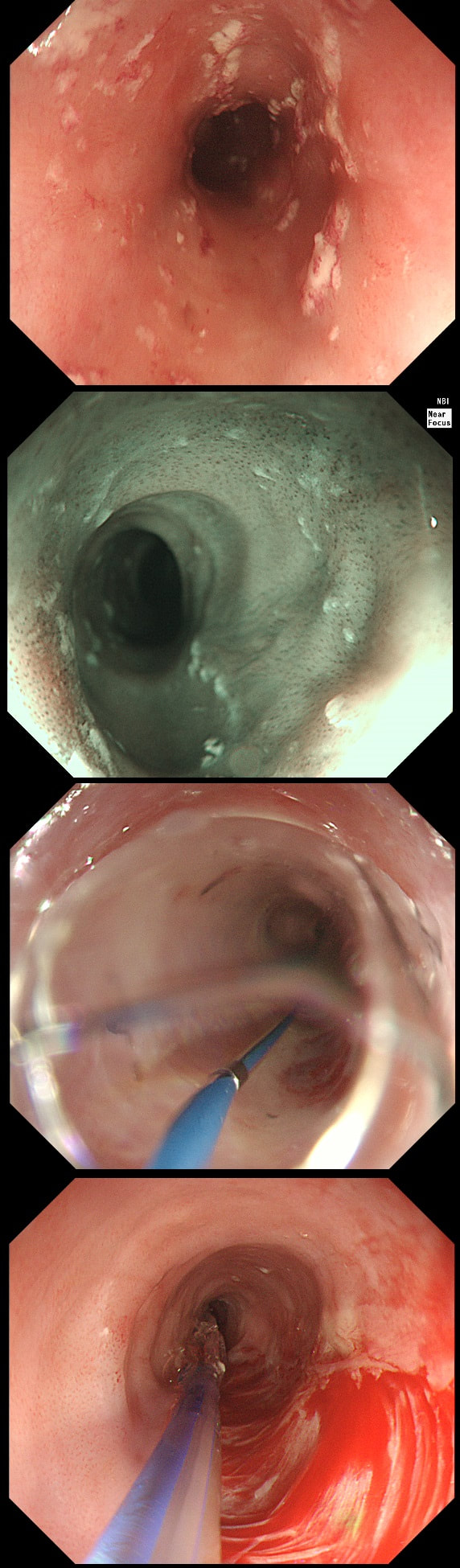

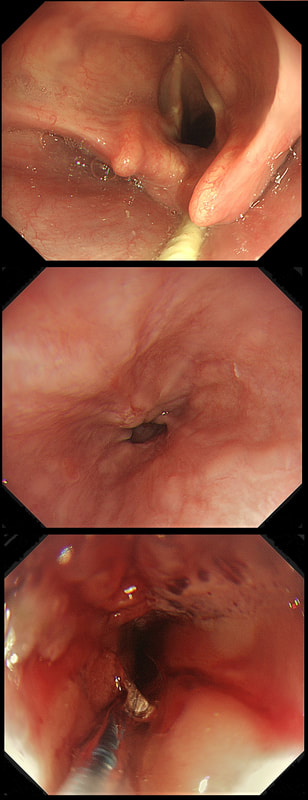

a) Reflux oesophagitis

An irregular squamo-columnar junction does suggest previous reflux oesophagitis but in this case there is more...

b) Non-dysplastic short segment Barrett's

Short-segment Barrett's is defined as Barrett's up to 3cm. In contrast, 'ultra-short Barrett's is less than 1cm. We sized the Barrett's as C0/M2 (according to the Prague classification). However, it doesn't look non-dysplastic!

c) Barrett's with intra-mucosal cancer

This would have been my own guess. There is no 'thickness' to the lesion and there is no ulceration, two features which would suggest that the lesion can't be removed endoscopically

d) Siewert II invasive cancer

Of course it may be invasive but that would be a little surprising. Endoscopically, this is IMca. Similarly HGD is unlikely as there is a lot of mucosal irregularity and you can see something has infiltrated below part of the squamous mucosa in the 2 o'clock position.

explanation

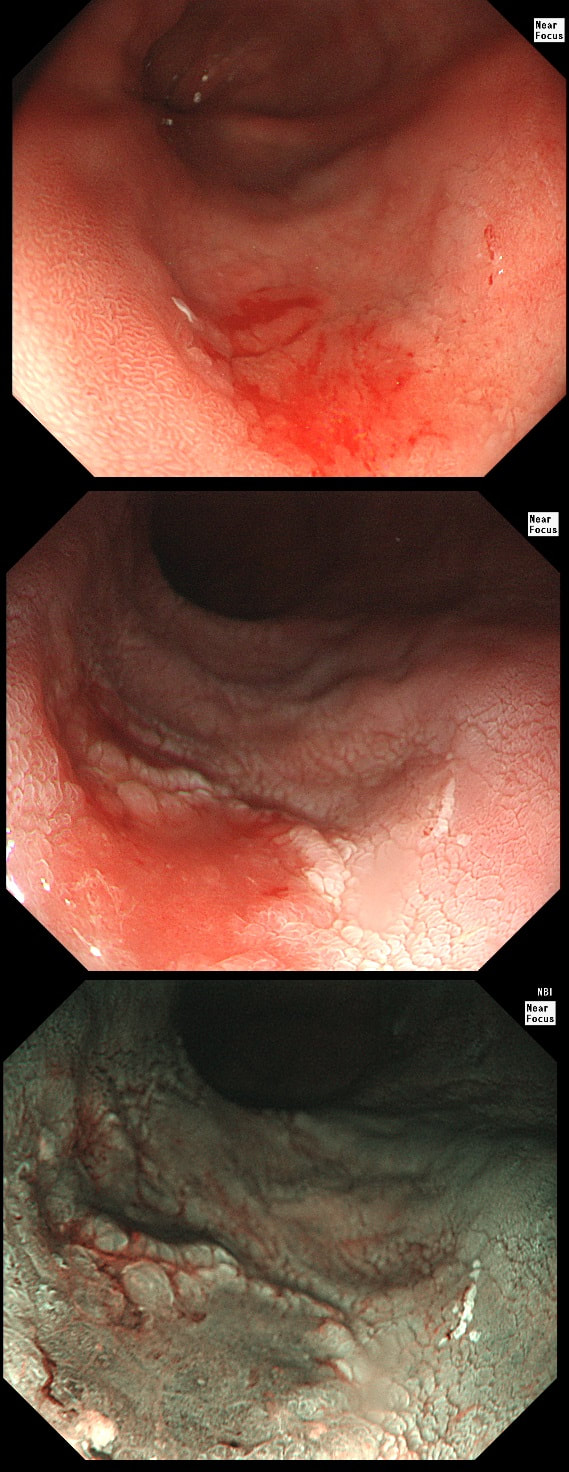

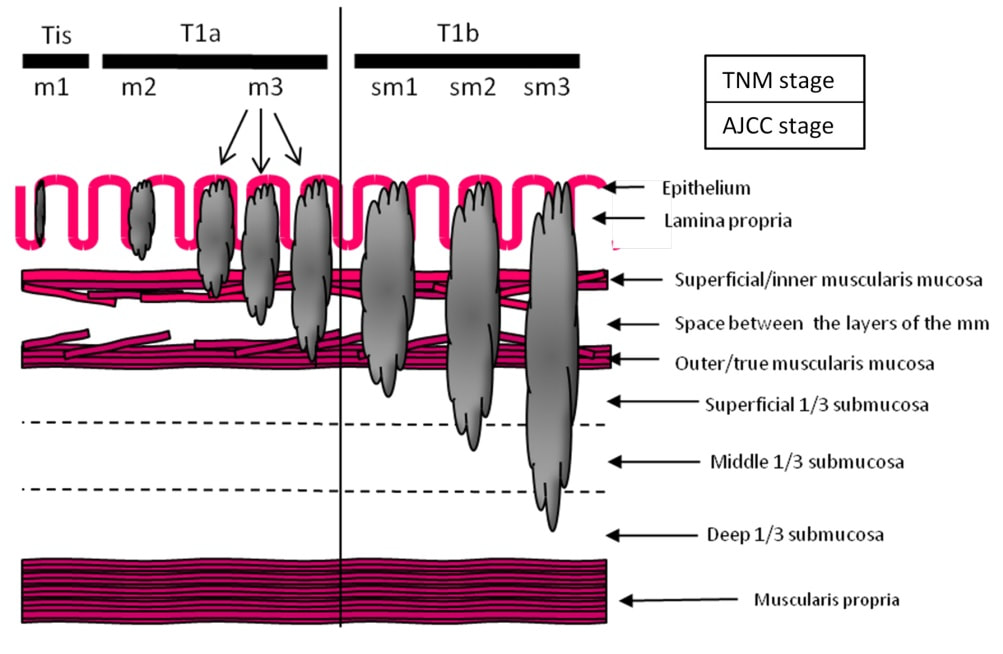

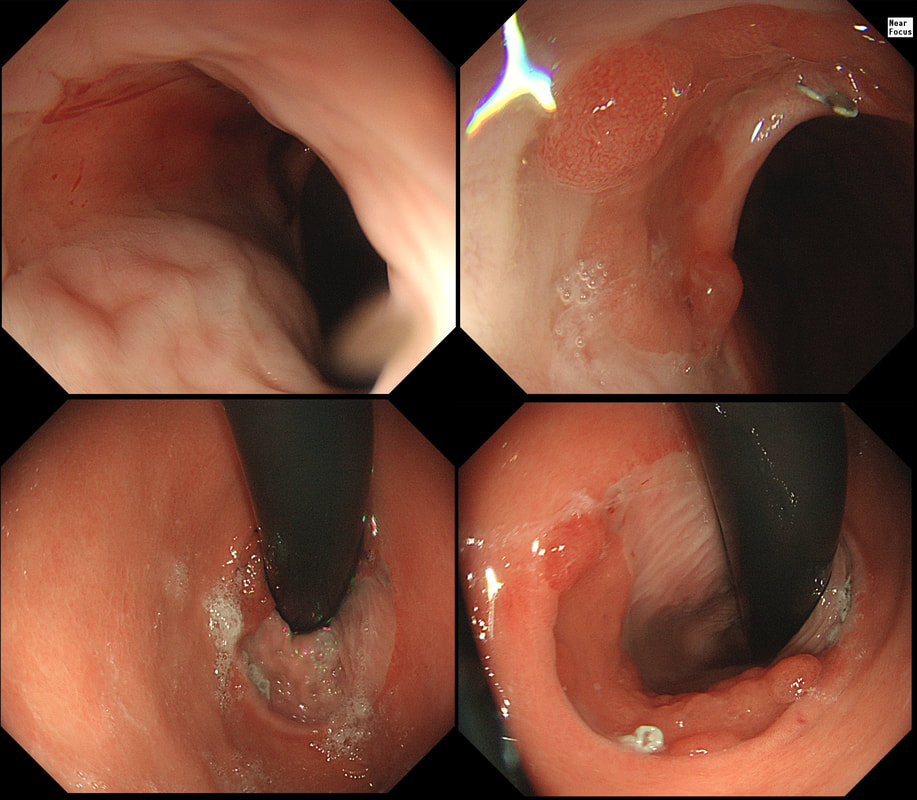

As you know, most of the time Barrett's neoplasia develops on the right-hand side and in the distal (rather than the proximal) Barrett's segment. In this case, in the 2 o'clock position there is a subtle mucosal irregularity. In fact, there appears to be something infiltrating below the squamous mucosa at this location. Biopsies had suggested IMca and a CT had been reassuring. Because the lesion is endoscopically resectable, we didn't bother with an EUS. The lesion was removed and confirmed as a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology. On the other hand, all margins were clear and there was no LVI (lympho-vascular invasion). In the hierarchy of poor prognostic features, LVI and depth of invasion (>500µm) are the most important whilst poor differentiation is the least important. Nevertheless, I was a little worried when the patient declined surgery...

This 'lesion' was barely visible within in a Barrett's segment on white light. However, after acetic acid and with NBI it's more obvious.

WHAT IS THE LIKELY HISTOLOGY?

a) Barrett's LGD

Usually invisible or just a red, flat patch

b) HGD

Subtle change in crypt pattern but with little nodularity?

c) IMca

This was my own guess but it was wrong...

d) Invasive cancer

Yes, superficial invasion (100 microns) and poor differentiation!

explanation

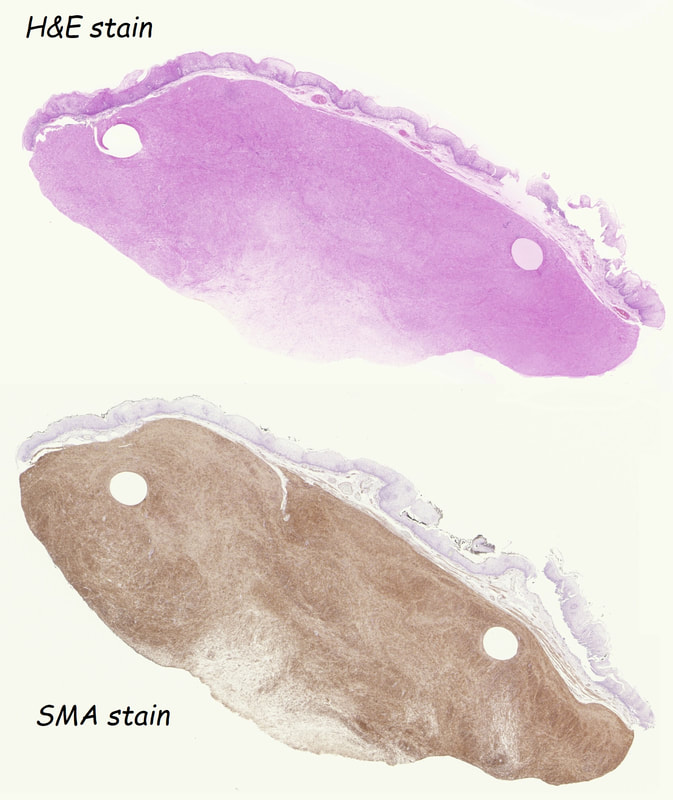

I removed this lesion without worrying too much about the subtle 'depressed' growth pattern and the small, round crypts in the centre of the lesion. However, I was surprised to see the pathology report of a superficially invading adenocarcinoma, with poor differentiation to boot!!! This finding makes the advice on 'further treatment' more complex. As you know, in both the upper and lower GI tract, the finding of 'lymphovascular invasion' (LV) is probably the most 'ominous sign' that a patient needs surgery (or chemo-radiotherapy in case of the oesophagus). Poor differentiation is 'bad', but less bad than LVI.

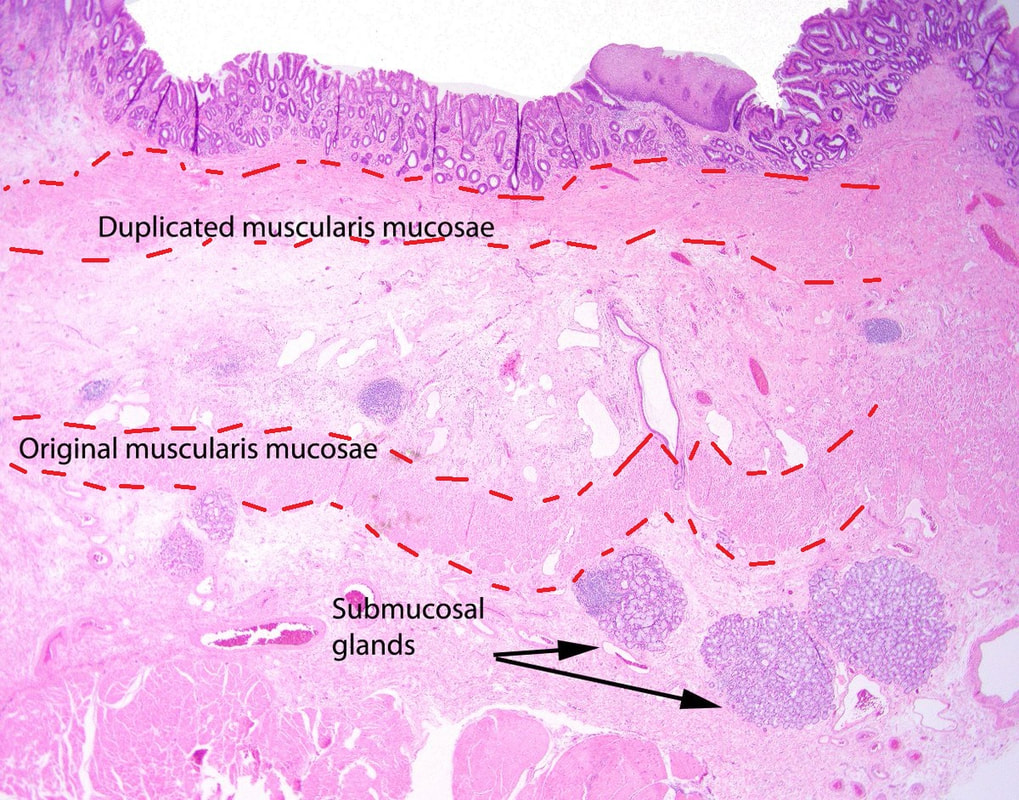

Depth of invasion is also important and in Barrett's you are 'allowed' invasion to about 500 microns below the muscularis mucosa. The corresponding 'safe margin' in SCC's is only 200microns. In this case the depth of invasion was only about 100 microns, leaving 'poor differentiation' as the only 'bad sign'. The patient wasn't a surgical candidate and refused CRT. This was 3 years ago and so far all is well! By the way, the histopathologists do have a more difficult job than you perhaps imagine, measuring the depth of invasion in Barrett's cancer. This is because they often see several bands of muscularis mucosa, so called 'duplication of the muscularis mucosa'. Elsewhere in the GI tract, the muscularis mucosa is a single band of smooth muscle. They measure the depth of invasion from the top of the muscularis mucosa down the the deepest point of invasion. However, if there are several bands of muscularis mucosa, which one do you measure from?!? Below is an example to illustrate the dilemma.

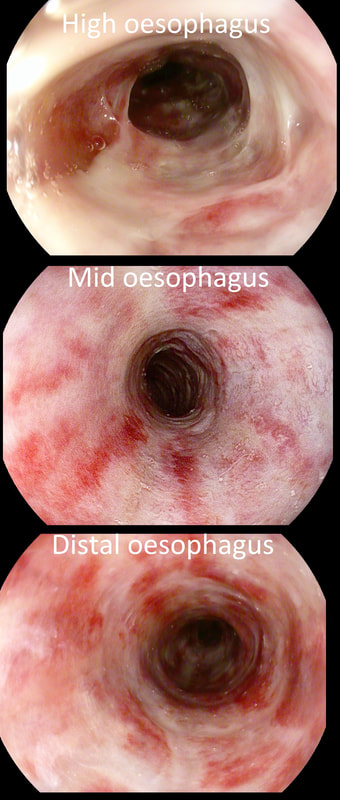

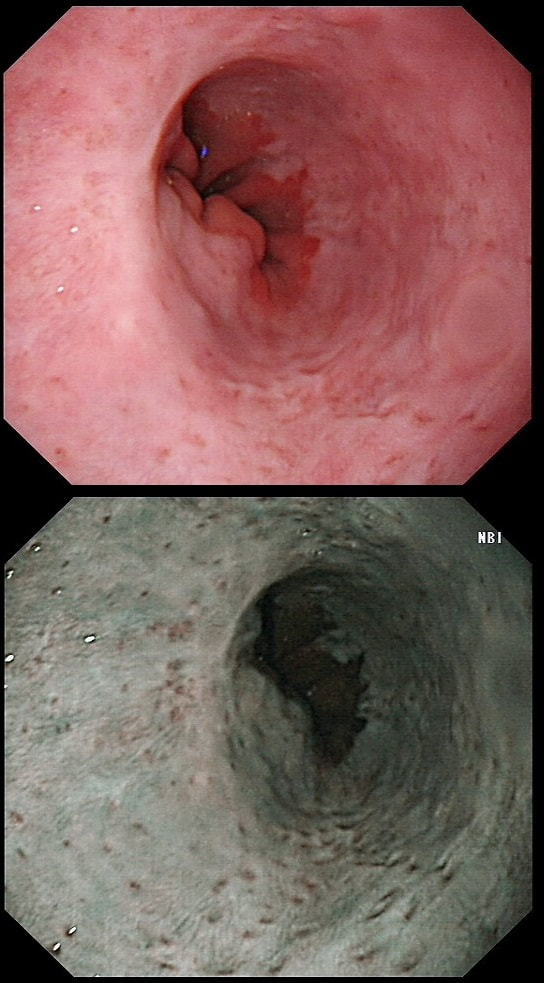

A somewhat scary dilatation.

WHAT IS THE LIKELY AETIOLOGY OF THE STRICTURE?

a) peptic stricture

There are no linear reflux ulcers!

b) eosinophilic oesophagitis

yes! Long and fusiform stricture and mucosa 'splits' in a frightening way

c) SCC

Those IPCL's do look a little prominent but not ectatic etc

d) adenocarcinoma

But the stricture is within the squamous part of the oesophagus!

explanation

Eosinophilic oesophagitis was first described in 1978 and is widely regarded as an allergic condition. Food allergy may play a significant role and the majority of sufferers have either personal or family history of other allergic conditions.

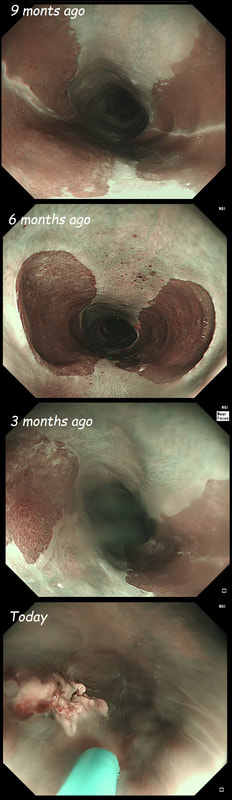

In contrast, Lymphocytic oesophagitis is much more recent, first described by Rubio et al in Sweden in 2006. As yet there is no consensus on how many lymphocytes are needed to make the diagnosis. Extrapolating from EoE, I take 2 samples from the proximal, middle and distal oesophagus respectively, in all patients with inexplicable dysphagia. LyC oesophagitis is still regarded as something of an entity "in search of a disease". For this reason it's difficult to know if the reported increasing prevalence is simply due to the pathologists being on the lookout and more oesophageal samples (correctly) being taken in patients with dysphagia. There is an association with old age, female gender, smoking, reflux disease and primary esophageal motility disorders. Clinically oesophageal rings, webs, nodularities, furrows and strictures have been described in both conditions. Personally, I think that they look subtly different! I suggest a LyC oesophagitis when there is subtle dilatation of the intrapapillary capillary loops within the squamous oesophagus. In my experience you don't usually see this in EoE. For this reason, a lymphocytic oesophagitis would have been a very reasonable guess in this case. Those IPCL's do look a little dilated don't they? Of course, strictures are supposedly far less common in LyC oesophagitis than in EoE. This patient attends for Barrett's surveillance WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

a) Barrett's without dysplasia

A nodule within Barrett's is NEVER 'normal'!

b) LGD

LGD is flat, not nodular!

c) HGD

Good guess! Although your guess actually proved to be wrong

d) IMca

Small crypts + nodule = correct!

e) invasive cancer

Nodule should have been larger and without those small crypt openings

explanation

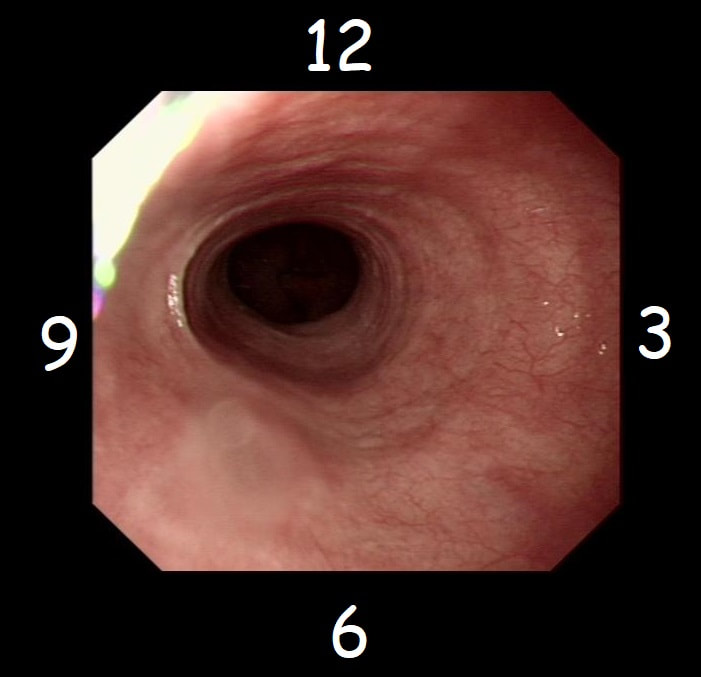

My 'rules of thumb' when assessing Barrett's is as follows: 1) crypts look different in a distinct patch but the area is flat = LGD 2) areas of superficial ulcers within the Barrett's = widespread LGD 3) crypts look different and there is a distinct nodule = HGD 4) crypts are tiny small and there is a nodule = IMca 5) there are no crypts and there is larger nodule = invasive cancer Of course this isn't fool proof ! After all, it's very difficult to distinguish HGD from IMca even on histology! However, it gives you a starting point on how to assess Barrett's and what you should enter on that Histopathology request form. Remember that your pathologists need your help! WHERE IS THE BARRETT'S CANCER?

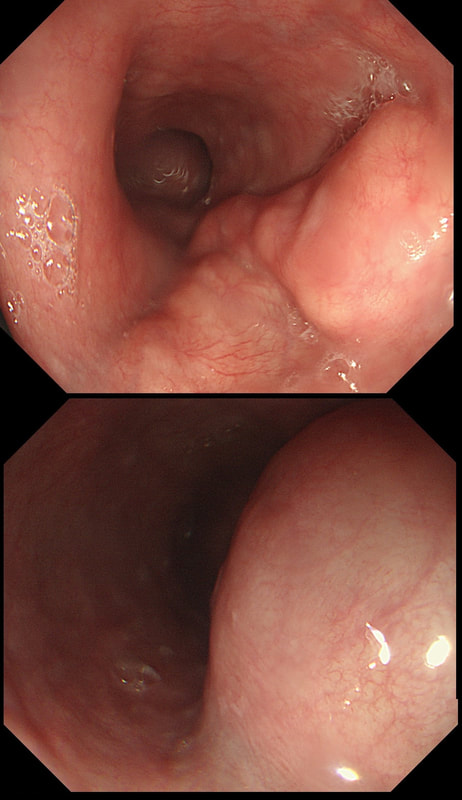

a) 12 O'clock

Eagle eye!

b) 3 O'clock

But the round crypt openings say otherwise!

c) 6 O'clock

Nope!

d) 9 O'clock

Where there is hardly any Barrett's?!

explanation

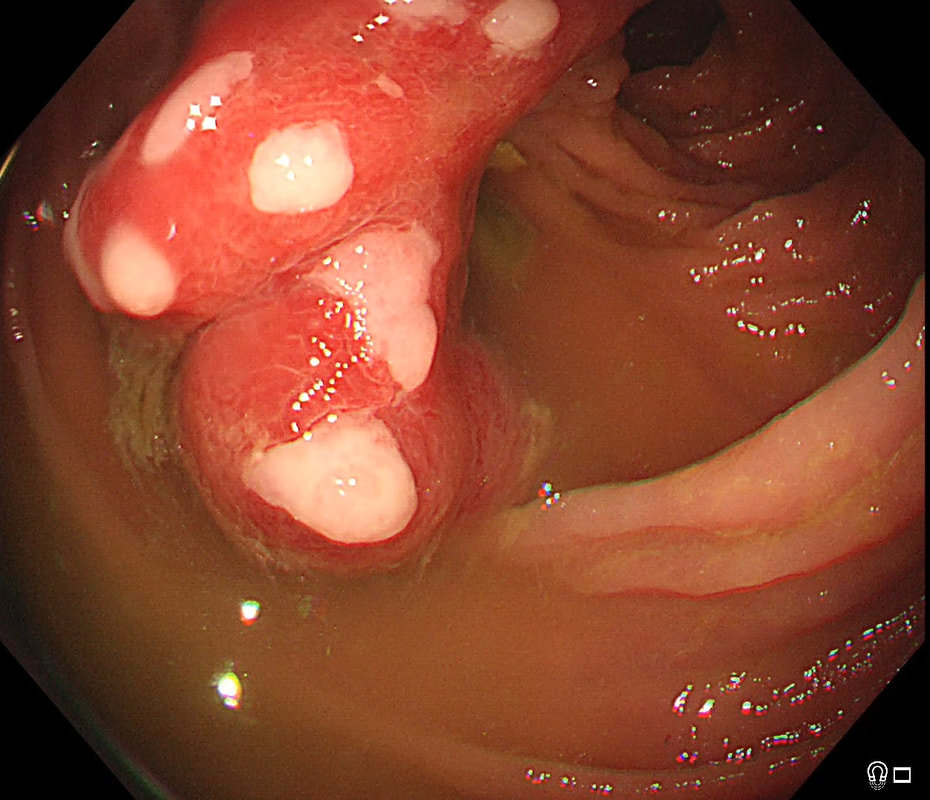

Of course the lesion is situated at 12 O'clock. There you can see a subtle mucosal nodularity with an irregular vessel pattern. It was removed by 'suck within the cap' EMR and confirmed as an IMca. This lesion is being removed from the distal oesophagus WHAT IS THE LIKELY HISTOLOGY?

a) Hyperplastic polyp

You must be joking!

b) Adenomatous polyp

A gastric adenomatous polyp would surely now be malignant

c) Early malignant polyp

But it's arising from a malignant flat component!!!

d) Advanced gastric cancer

Absolutely!

explanation

Of course this is all very odd. Clearly this is an advanced cancer at the GOJ. What business do I have in 'attacking' this endoscopically?! Actually, the elderly patient had completed a course of chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for a T2, N0 junctional adenocarcinoma some 30 months previously. Now he has developed dysphagia and a CT confirmed a 2cm polyp at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Histology had shown 'at least IMca' and he was referred for consideration of an endoscopic resection. Clearly this lesion can't be cured endoscopically. In fact, the elderly patient is not a candidate for surgery and therefore there is no cure at all. However, I was thinking that as the cancer is mainly polypoidal, perhaps if the nodule could be removed, his swallowing will improve and he will not need a stent and could be offered brachytherapy. Clearly this was all 'speculative' but I'm glad to say that 6 months later, the patient still has not developed any dysphagia and his now starting brachytherapy. No doubt a better outcome than could be offered by a stent? An odd lesion in the middle of the oesophagus of a 55 year old woman. WHICH OF THESE POSSIBILITIES IS THE MOST LIKELY?

a) Papilloma

Papillomas look more warty and I've never seen them ulcerate

b) Leiomyoma

Statistically the most likely benign lesion probably!

c) GIST

Are very rare in the oesophagus!!!

d) NET

Are also very rare in the oesophagus!

e) SCC

Not likely as the IPCL's are regular and the lesion isn't brownish!

explanation

GIST's are extremely rare in the oesophagus whilst common in the stomach. In contrast, leiomyomas are common in the oesophagus and rare in the stomach. However, this looks odd and the previous biopsies had not been able to get to the bottom of the diagnosis. Are we missing a SCC? However, it looks like something from deeper layers were breaking through the mucosal surface. In contrast an SCC should start growing at the surface and in time invade deeper. The 'intrapapillary capillary loops (IPCL's) dilate up, become irregular and eventually completely disorganised in SCC's. At the same time the oesophageal wall takes on a brownish tint on NBI.

I decided to remove it and it turned out to be a leiomyoma. I presume that it had got traumatised or perhaps by pressure necrosis ended up with a funny surface. Don't think that I have seen an oesophageal NET as yet. Presumably they are very rare in this location. By the way, I've uploaded an example of a T2 mid-oesophageal SCC in the clip below. The lesion looks smallish but is already beyond endoscopic cure and Lugol's shows up a large area of background dysplasia which looks orange rather than brown after Lugol's dye spray. This patient is attending for dilatation of a high oesophageal stricture but there is a surprise. WHAT IS THE CAUSE OF THE STRICTURING?

■ Corrosive ingestion

Yes, a likely cause of 2 high oesophageal strictures

■ Peptic ulceration

In the high oesophagus?!?

■ Lichen planus

Possible but never seen two !

■ Eosinophilic oesophagitis

They are not short and membrane-like!

■ SCC

The mucosa is unremarkable!!!

explanation

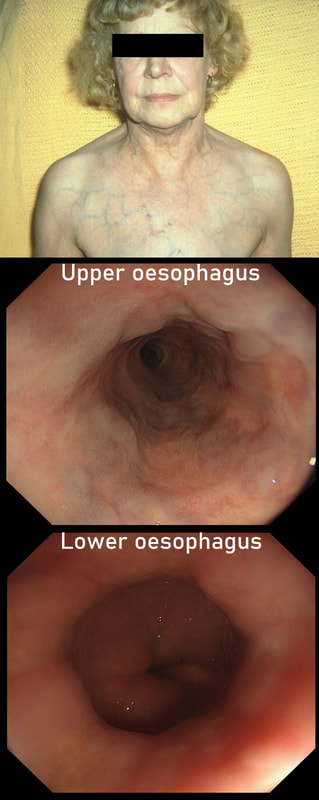

The 'surprise finding' is of course that there are TWO strictures some 2-3cm apart in the high oesophagus. All of the above could be the cause, I guess. Of course, the stricture does not look malignant. Eosinophilic oesophagitis gives smoother, long tapering strictures, not short membrane-like strictures like this. Peptic ulceration would be unlikely in the high oesophagus (unless there is a long stretch of Barrett's below). Lichen planus is a possibility but the fact that there are more than one strictures, makes corrosive ingestion the most likely diagnosis. Actually, the patient had been admitted after swallowing a lot of toilet cleaner a few months earlier.

in the images below you can see what her oesophagus looked like after that alkaline burn. I wonder if giving a reducing dose of steroid, like we do after large oesophageal EMR's could have prevented her stricture? This patient is undergoing a set of oesophageal dilatations of a radiotherapy induced stricture. Three set of samples, a total of 18 biopsies have been obtained from the stricture which have all been reassuring. A CT has reported: "Distal oesophageal mural thickening extends throughout the length of the previously demonstrated bulky oesophageal tumour. No focal abnormality to suggest recurrent disease and presumably appearances are all radiotherapy related". In the video clip, the stricture is seen to be dilated to 20mm. WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT

■ Organise the next dilatation in a weeks time

She WILL need more dilatations but you've missed something important!

■ Take another set of samples from that stricture

It does look concerning still but there is something even more concerning here!

■ Take another set of samples from the more proximal oesophagus

You've spotted it!

■ Take samples at the distal oesophagus (below the stricture)

That odd, fleshy lump at 6 O'clock below the stricture has been sampled already. More samples is never wrong but there is something even more important to sample first!

explanation

On intubation, I glimpsed something just below the upper oesophageal sphincter. I deliberately didn't dwell on it in the video, simulating the previous intubations when a synchronous lesion had been missed. In the explanatory clip below, you get a better view of her second SCC. CT staged the second lesion as no worse than T2, N0.

The moral of the story? It's when we are distracted that we run the risk of missing things! In this case, the previous endoscopists had approached the endoscopy as a case of dilatation and switched off their eyes! This is the GOJ of a 60 yr old woman with dyspepsia. WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

■ Reflux oesophagitis

No this is a nodule not an ulcer!

■ Hyperplastic/reactive nodule

Hyperplastic nodules have villous surface!

■ Unremarkable Barrett's

A nodule within Barrett's is always suspicious!

■ Adenocarcinoma

Absolutely!

■ Squamous cell carcinoma

No abnormal vessel pattern within nearby squamous mucosa!

Explanation

Actually, this patient was on a Barrett's surveillance programme. Five years earlier a small IMca had been removed following which annual surveillance had been reassuring. However, then this lesion was found and referred for removal.

Histological assessment of the resection fragment reported early invasion into the submucosa (which is 'allowed' provided that the depth of invasion is less than 500 microns (0.5mm). There was no LVI but unfortunately, there was poor differentiation. Of course, the 'worst' feature to find is probably LVI. Poor differentiation is worrying but less worrying than LVI. The reason for this is that 'poor differentiation' is a rather poorly defined entity. For example, how many crypts should be involved to call something 'poor differentiation' rather than 'focally poor differentiation'? Anyway, the patient was young and ultimately underwent an Ivor-Lewis which confirmed that the EMR had been curative with only some HGD remaining within the residual short stretch of Barrett's. We urgently need a prospective study following this type of Barrett's patient closely over time with regular EUS and CT to see if we can detect the small number of patients who subsequently turn out to have lymphnode involvement

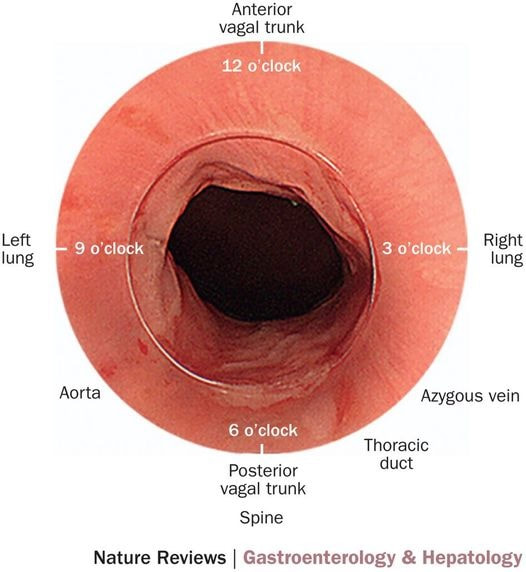

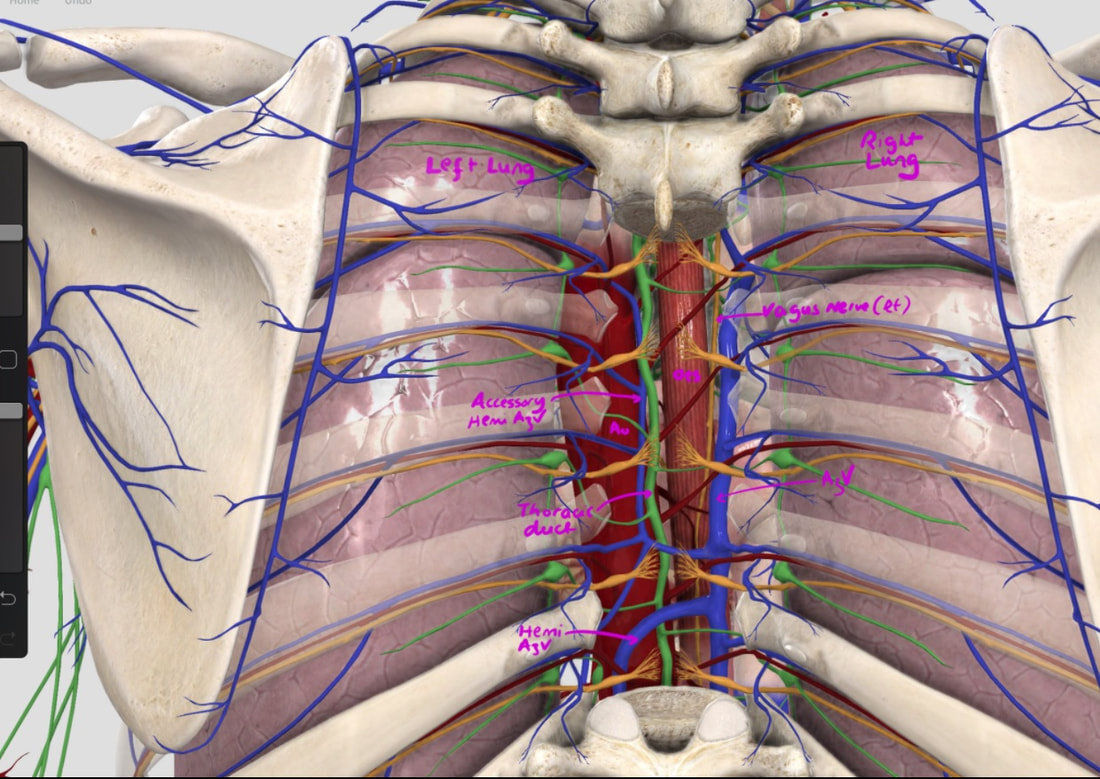

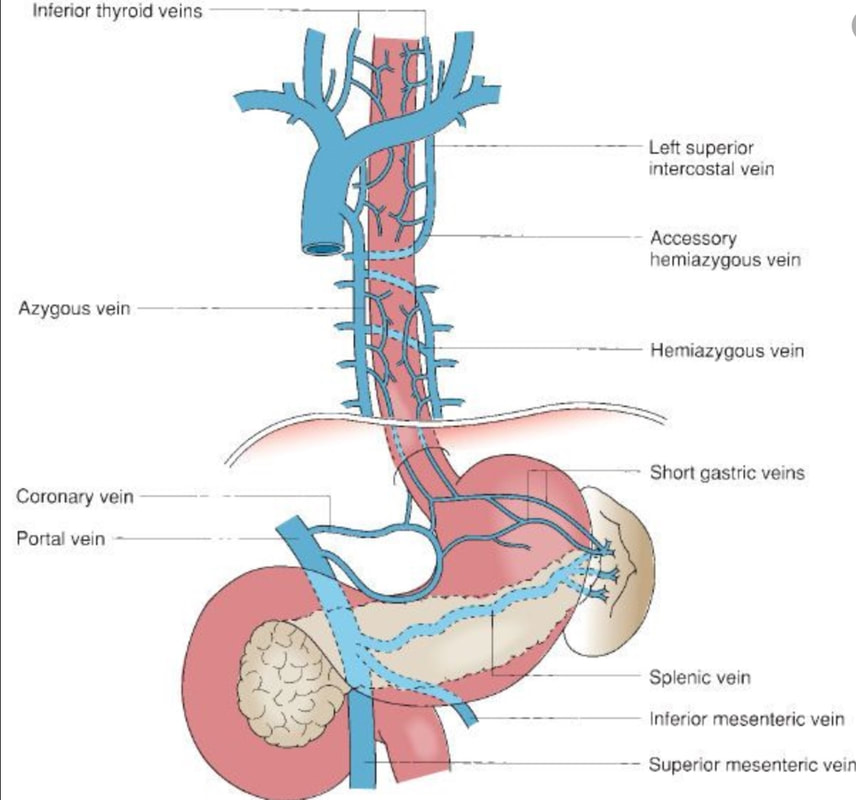

With POEM, knowing the landmarks outside of the oesophagus has become something which endoscopists are expected to be familiar with. Here is a quick self-test!

AT WHICH POSITION OF THE 'CLOCKFACE' DO YOU FIND THE:

■ Spine

6 o'clock

■ Anterior vagal trunk

12 o'clock

■ Posterior vagal trunk

6 o'clock

■ Thoracic duct

5 o'clock

■ Left lung

9 o'clock

■ Aorta

7-8 o'clock

■ Azygous vein

4 o'clock - runs in the posterior mediastinum, on the right side of thoracic vertebral column. It drains into the SVC, and returns blood from the posterior walls of the thorax and the abdomen.

This 50 year old lady presents with dysphagia and a distal oesophageal stricture is confirmed. Intubation is a little tricky due to a pharyngeal pouch but we managed to intubate the oesophagus after the successful passage of a guidewire. After you have obtained a set of samples (last photo), the patient asks what will happen next.

WHAT IS YOUR REPLY?

■ Too early to tell, we will await analysis of the samples first

It's not too early to tell - the signs are there!

■ Whilst we await histology, I will request at CT

Good man! And organise a cancer MDT discussion!

■ The analysis will probably be reassuring and in all likelihood a dilatation is next

Sadly, this is unlikely !

■ The pouch is more likely to be the main problem than the stricture

No, that's not it!

explanation

The stricture doesn't look quite right does it? Somewhat 'nobbly' and without associated reflux oesophagitis. This stricture looks malignant ! There is one more concerning feature which you may have missed...

The vocal cord on the left-hand side is weaker than the right! On direct questioning, the patient confirmed that her voice had recently changed and become more hoarse! This patient had an advanced oesophageal cancer with metastases to the high lymphnodes on the left causing a recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis! Out of the four options, organising a staging CT and referral to the UGI cancer MDT is the correct course of action!

The squamous portion of this oesophagus looks very unusual !

WHAT IS THE LIKELY REASON FOR THIS APPEARANCE?

■ Previous reflux disease

Nope, that's not it!

■ Previous EMR

Gives a pale scar, usually covered with squamous mucosa

■ Previous RFA

Absolutely. You've also seen it?

■ Previous radiotherapy

Gives telangioectatic vessels!

explanation

This patient had undergone RFA, leaving the squamous mucosa looking a little odd. It's actually the openings of the 'oesophageal glands' which you can see. In my experience, there is no point in taking any samples as histology will be reported as normal. In most cases, Barrett's returns at the gastro-oesophageal junction. The return is slow and subtle and for this reason you should take samples from what appears to be the 'columnar side' of the squamo-columnar junction. As intestinal metaplasia (Goblet cells to you and me) are common at the cardia, the pathologists will not be able to tell you if the Barrett's is returning. However, they CAN tell you if the epithelium look dysplastic again!

In a minority of cases, perhaps 1:4 the recurrence happens below the squamous mucosa which can be very hard to see. Of course, the only way to deal with 'buried Barrett's', is to remove the patch by EMR!

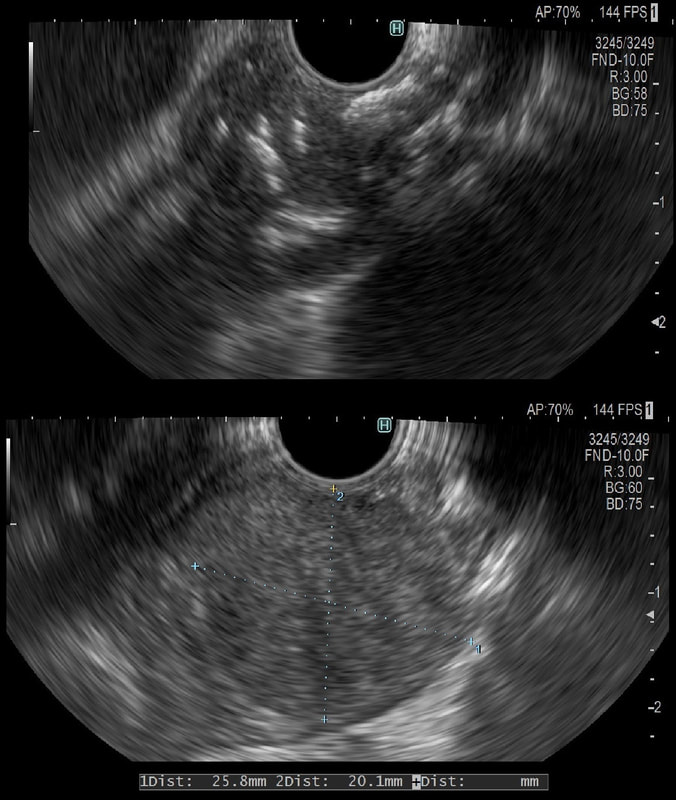

This was an incidental finding in the mid-oesophagus. Subsequently an EUS is organised and the lesion is ultimately removed (histology in the last image)

WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSIS?

■ Neuroendocrine tumour

I've never actually seen an oesophageal NET

■ Granular cell tumour

But it isn't a small white submucosal disc?!

■ Leiomyoma

A shrewd guess!

■ GIST

These are VERY rare in the oesophagus (but common in stomach)

■ Melanoma

Usually look brownish endoscopically!

explanation

Leiomyomas are the most common submucosal lesion found in the oesophagus. No idea why they are so rare in the stomach, where GIST's are the most common submucosal lesion. Correspondingly GIST's are very rare in the oesophagus.

These usually arise from the circular muscle propria layer. On CT they are often calcified and there are of course no nearby nodes to suggest malignant disease. Indeed, malignant transformation is extremely rare and for this reason many centres would ignore a small submucosal lesion such as this, when found in an elderly person. Larger (around 5cm usually) and symptomatic lesions (which are more likely to be leiomyosarcomas) are enucleated surgically. "- They shell out like peas" according to one of our UGI surgeons. However, our local surgeons are also careful to point out that resection usually result in some damage to the muscle propria layer, which require repair as otherwise a diverticulum may develop. With endoscopists spending more time in the 'third oesophageal space' (i.e. the submucosal space), doing ESD's and POEM, the suggestion that we should also remove leiomyomas endoscopically has arisen. May seem like a good idea but I would advocate caution for the simple reason that endoscopically, we are unable to repair the defect we cause in the muscle propria layer ... Oh, how about that 'SMA stain' used in the histology. This is 'Smooth Muscle Actin' stain which does exactly what it says on the tin ...

This is something of an enigmatic image of significant problem. It may not look like a problem ..

WHAT DOES IT SHOW?

■ Barrett's oesophagus

Of course!

■ Local recurrence at anastomosis

It IS an anastomosis !

■ Fistula

Fistula's are usually very obvious in the oesophagus but difficult to spot in the rectum

■ Squamous dysplasia

That is normal squamous mucosa !

explanation

The trick is to work out what's happened! Of course, this patient has undergone an 'Ivor-Lewis' oesophagectomy for oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Unfortunately, the surgical anastomosis between the mid-oesophagus and the 'gastric tube' wasn't quite high enough and the surgeon has left a small patch of Barrett's behind. Potentially a ticking time bomb !

Fortunately, it should be possible to remove this small patch of Barrett's by either an EMR or RFA. I think that the Barrett's is a little too nodular (histology reported LGD), and we therefore opted for an EMR rather than RFA. This patient has been referred for a dilatation WHAT IS THE AETIOLOGY OF THE STRICTURE?

■ Peptic stricture

Too membrane-like to be peptic

■ Schatzki ring

Of course it is - Well Done!

■ Eosinophilic oesophagitis

Strictures in EoE are long and tapered

■ Radiotherapy stricture

RXT strictures are at least a couple of cm in length

■ Malignant stricture

Of course it isn't !

explanation

This short almost membrane-like stricture is of course a Schatzki ring, named after the German-American physician Dr Richard Schatzki. It's usually easy to treat these with a balloon dilatation. This particular case is unusual as two dilatations were required. However, rather than going ahead with a second dilatation to 20mm (our largest balloon in Leeds), I decided to cut the membrane with the tip of a snare and the diathermy set on the normal sphincterotomy setting.

The uploaded video is a good example of this mishap when cutting across yourself. I don't think that I perforated the full thickness of the oesophagus but applied a clip just in case (I've never regretted placing too many clips).

These are the NBI images of a young woman complaining of chest pain, dysphagia and reflux symptoms. She also complains of feeling of a 'lump at the back of her throat'.

WHAT WAS THE ORIGINAL DIAGNOSIS?

■ Reflux oesophagitis

Would be an odd pattern surely?

■ Barrett's oesophagus

With squamous mucosa below?

■ Eosinophilic oesophagitis

EoE doesn't look brown on NBI !

■ Oesophageal inlet patch

Yes, but why is it getting smaller?

■ Squamous dysplasia

No dilated IPCL's !!!

explanation

This patient was found to have a large oesophageal inlet patch at the index endoscopy a year ago. Although his symptoms were rather mixed, we have spent 4 sessions on ablating her inlet patch with APC.

Of course, how often you find these will depend on whether you use NBI/FICE/BLE during extubation. Of course you should do because you are then less likely to miss squamous dysplasia! An interesting study reported that gastric inlet patches contained glucagon cells which would normally only be found in the embryo and subsequently disappear. To remind you, the hormone glucagon is normally produced by the alpha cells of the pancreas! Glucagon-like peptide-1 is also secreted by some cells in the ileum and colon. Anyway, the implication is that the gastric inlet mucosa is actually an embryonic left-over. Interestingly, there appears to be a lower prevalence reported in older populations, and some authors suggest that inlet patches may regress with age! Seems odd for a congenital condition? Endoscopic studies have found inlet patches in up to 10% of patients. Whether these give rise to any symptoms is contentious. It has been suggested that inlet patches may give rise to globus sensation due to irritation of the upper oesophageal sphincter by acid or mucus. Furthermore, others have suggested that H. pylori colonization of the heterotopic gastric mucosa causes symptoms. Others believe that it's not just the upper oesophageal sphincter which is abnormal but the entire oesophageal motility may be disorganised in these patients. However, prospective studies have usually not found that patients in whom an inlet patch is found, present with any different symptoms compared to patient without an inlet patch. Of course as anywhere in the body, cancer may develop. A study in Digestive Diseases & Sciences [2018;63(2):452-65] reported on 156,236 gastroscopies and may have found 3 cases of malignant conversion. Assuming that 10% of their patients had an inlet patch, that would suggest that you would have to regularly surveil 500 patients with an inlet patch over many years detect 1 cancer. If you grab 500 random people off a street and scope them annually for 5 years, wouldn't you pick up more than a single early oesophageal cancer? Seems like that lemon is not worth the squeeze? Finally, how about our patient? Over the period of one year, we spent about one hour ablating and completely getting rid of that large inlet patch (well two inlet patches really). The patient reported that symptoms were much better for a couple of months but then returned as before. Of course as she no longer has an inlet patch, we can now conclude that it never did contribute to her symptoms. Must admit that I was sceptical from the start! Show me a prospective RCT with evidence that ablation provides a clinically significant improvement in patients globus symptoms for more than a few months! Until I see that RCT, I will not be offering ablation for these patients.

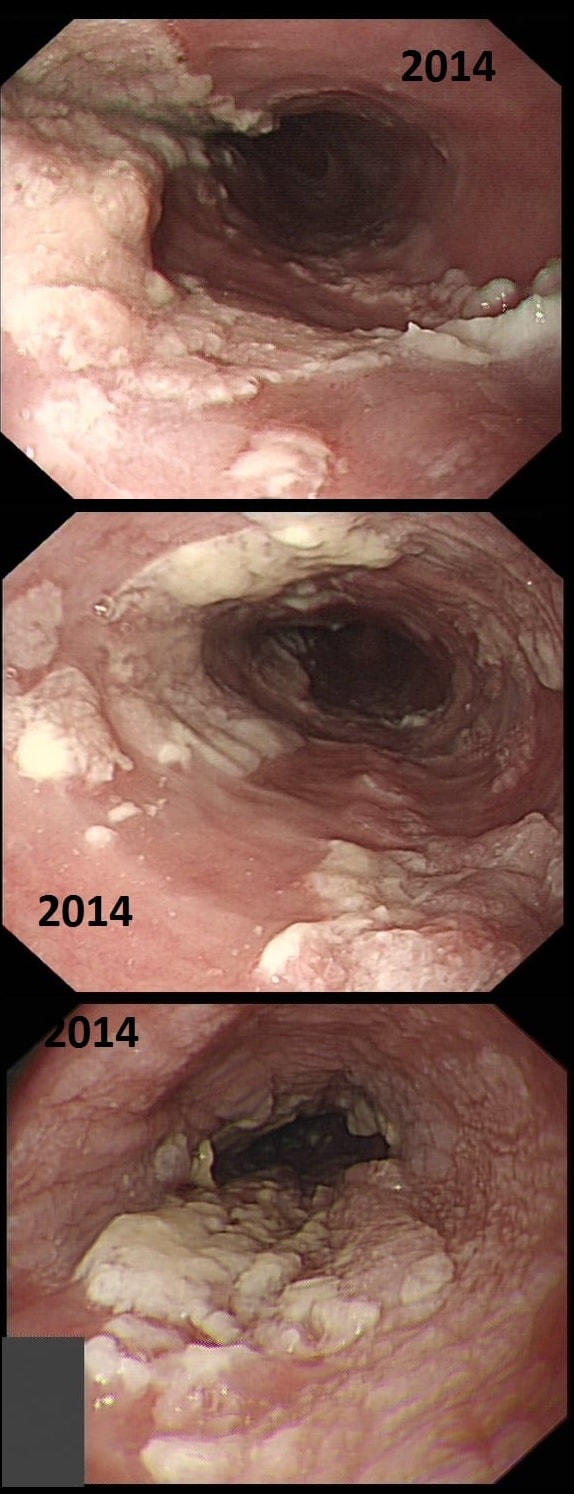

This patient presented with odynophagia and this is the appearance of the oesophagus from 2014

WHAT WAS THE INITIAL DIAGNOSIS IN 2014 ?

■ Candidiasis

These lesions or to 'fleshy'!

■ Reflux oesophagitis

The lesions are too 'fleshy'!

■ Eosinophilic oesophagitis

Doesn't explain the 'lumpiness' of the mucosa

■ Oesophageal papilloma

A papilloma gone mad !

explanation

This is a case from Pradeep Mundre at Bradford. The correct diagnosis was 'Diffuse oesophageal Squamous papillomatosis'. Unfortunately, by 2021 the patient re-presented with worsening symptoms was was found to have developed a 'basaloid squamous cell carcinoma' (photo below).

Squamous Papillomas and Squamous papillomatosis of oesophagus Papillomas are finger-like projections that histologically have a central fibrovascular core surrounded by proliferative squamous epithelium with keratin outside this. Of course these are usually small and isolated. However they can become larger and rarely there is diffuse changes as in this case, and term 'oesophageal papillomatosis' is applied. There is little in the published literature on oesophageal papillomas with just a few published case series. Aetiology is unclear as to why some grow large whilst the vast majority remain tiny. Published literature has been conflicting with regards to association of oesophageal papillomas with HPV infection. Clinical relevance, natural history and whether this is a premalignant lesion, remain a matter of debate. There has been a few case reports of progression/ association with squamous cell carcinoma, especially with diffuse squamous papillomatosis. In other organs, the causal link between human papillomavirus infection and cervical, anogenital, and some oropharyngeal malignancies has been established by both molecular and epidemiological data. Management Owing to paucity of evidence, it is unclear how to manage this. I guess we can translate knowledge from other areas and use this in oesophagus Isolated small papillomas are easy to ablate with a quick 'zap' of APC. For larger areas of more diffuse papillomatosis, ablative techniques, such as APC ablation or cryoablation or radiofrequency ablation may all be considered. However biopsies or even EMR may be prudent of more 'chunky' areas to rule out possibility of 'prevalent' dysplasia/malignancy. Bjorn has treated a couple of patients with very large areas of oesophageal squamous papillomatosis with APC ablation. Of course, it's quite daunting when you start and it takes a special patient not to freak out when belching up the fumes of vaporised mucosa (a GA would make it easier for the patient of course). However, these lesions actually turn out to be easy to ablate and you will be surprised at the progress when the patient returns for a re-check (usually about 3 months later). However, most patients will probably require 3-4 sessions when the surface area involved is extensive as in this case. Of course, it's difficult to give a general advice about management. Clearly the risk of an elderly patient living long enough to develop a SCC must be small. Conversely, in a young patient, ablation to try to clear the oesophagus will avoid the need for surveillance and is probably justified. Reference Alomari et al Successful Treatment of Extensive oesophageal Squamous Papillomatosis With Cryotherapy, ACG Case Reports Journal: March 2019 - Volume 6 - Issue 3 'Banding EMR of this junctional lesion is not going to plan! Biopsies had diagnosed IMca at least but both EUS and CT had been reassuring. WHAT WOULD YOU CONSIDER NEXT?

■ Inject below lesion and try again

It will not work here and (rarely works at all)

■ Change to a wider cap

Will not work!

■ Remove lesion by ESD

You are asking for trouble!

■ Bail and declare that lesion is beyond endoscopic cure

There is no shame in admitting when you are beaten!

explanation

Although EUS and CT had both been reassuring, this lesion is clearly tethered down to the oesophageal wall. The lesion is extending too deeply for endoscopic cure. Trying to 'push the boat out' by attempting removal by 'pull within the snare' technique or ESD will fail and will run the risk of perforation, potentially resulting in the upstaging of the lesion. Bail out !

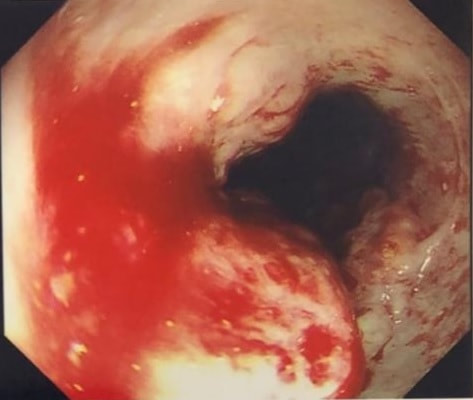

This lady is undergoing a gastroscopy

WHAT IS THE LIKELY DIAGNOSIS?

■ Cirrhosis and portal hypertension

Look again!

■ Splenic vein thrombosis

Gives you gastric varices!

■ Hepatic vein thrombosis

Pts present with ascites and normal LFT's!

■ SVC obstruction

Too easy perhaps?

explanation

‘Downhill oesophageal varices’ are associated with superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction or obstruction or as in this particular endoscopic case, a clot in the right brachiocephalic, subclavian and axillary veins. I thought that just showing the oesophagus would make the question too difficult and therefore added the photo of a patient with SVC obstruction. Perhaps this made it too easy ☺!

Venous drainage of the oesophagus is through the azygos and hemiazygos veins (see below). When there is thrombus, retrograde flow pushes blood towards the heart via collateral channels. If the obstruction is above the level of the azygous vein, varices develop in the upper oesophagus. However, if the clot is below, or involves the azygous vein, varices will form along the entire oesophagus. Bleeding is rare as varices in the proximal oesophagus are situated deeper within the submucosa than distal varices. However, if you are asked to deal with bleeding, you need to place bands at the proximal end of the varix. Sclerotherapy is contraindicated in the high oesophagus because of the risk of spinal cord infarction and vertebral infarction. Glue injection should also be avoided as there has been a case report of a massive PE.

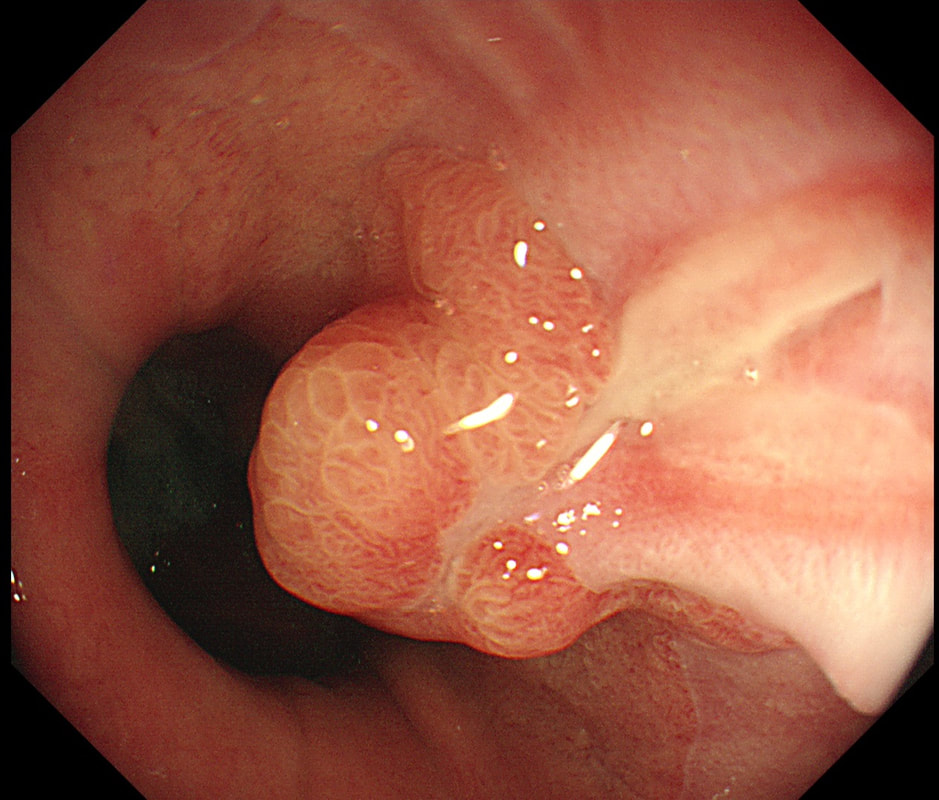

This patient was referred for an OGD after complaining of dyspepsia improving with PPI. This nodule is noted at the GOJ

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY DIAGNOSIS?

■ Hyperplastic/Inflammatory polyp

A shrewd guess!

■ Adenomatous polyp

Never seen one at the GOJ!

■ Dysplastic polyp

That villous surface is reassuring and makes it more likely to be inflammatory!

■ Superficial SCC

SCC's never have a villous surface like this!

■ Superficial adenocarcinoma

Villous surface and nearby reflux ulcer makes it unlikely

explanation

At first, that 'villous' surface may look disconcerting. However, you should know that in the oesophagus and stomach, polyps arising due to inflammation and oedema, (so called 'reactive or 'inflammatory' or 'hyperplastic' polyps) usually have a villous or gyrate surface pattern. In the stomach, these polyps often have an angrily red appearance and some white blobs making them look a little like pretty mushrooms (see example below).

OK, if this polyp is 'inflammatory', why is there inflammation? You can see a linear reflux ulcer in the 3 O'clock position. THIS is the reason for the inflammatory polyp. Of course, you'll take a couple of biopsies but as always, make an Endoscopic Diagnosis! You ARE a Professional and NOT a simple technitian unthinkingly feeding biopsies to the guys with brains!

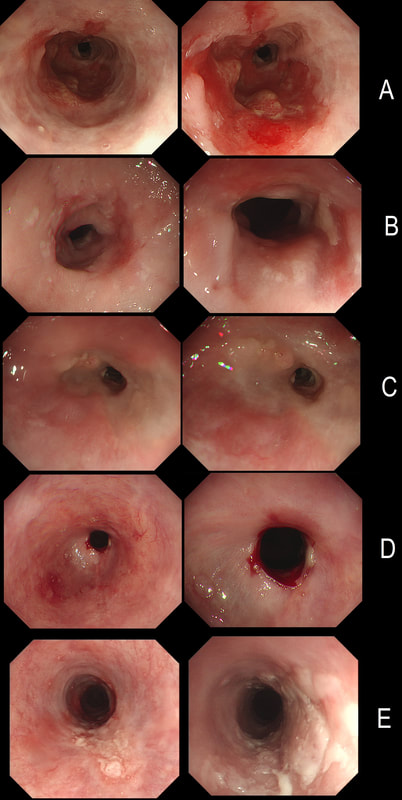

Here are 5 oesophageal strictures.

HOW MANY SHOW A CANCER?

■ 1 photograph

Try again!

■ 2 photographs

YES! Well done!!!

■ 3 photographs

No, image C does look dodgy I admit but was benign...

■ 4 photographs

There are 4 dodgy looking strictures but not all 4 were malignant !

■ 5 photographs

One stricture (image D) definitely looks benign!

explanation

Actually there are 2 cancers in there (case A and E). In order the aetiologies of the strictures are:

A = Adenocarcinoma B = Post radiotherapy stricture C = Peptic stricture D = Post ESD stricture E = Squamous cell carcinoma This 65 yr old patient attends following EMR of an IMca for RFA WHAT WOULD YOU DO NOW?

■ Go ahead and RFA

No that nodule is a show-stopper!

■ First take another set of biopsies

Or go ahead and EMR!

explanation

The BSG guideline as of 2013 (and updated on the topic of RFA for LGD in 2015), is very simple; RFA may be offered for flat dysplasia. The reality is often a little less clear-cut. For example, dysplastic Barrett's often appear slightly lumpy or with areas of superficial ulceration. When does a 'bumpy Barrett's' cross over into 'non-flat dysplasia'? I think that this is an example of 'not flat enough for RFA'. In fact, analysis of the original EMR specimen had reported a positive lateral margin! Expecting a local recurrence I actually went straight ahead and EMR'd the nodule which was confirmed as IMca. You will get the odd patient with Barrett's who fails to get his RFA because each time there is another little nodule to remove. Of course there are no hard and fast rules but these patients probably have 'bad disease' and are better served by an oesophagectomy. Of course, many of these are too old for surgery in which case you have no option but to keep nibbling away at their Barrett's mucosa until some adverse histological feature sends them along for chemoradiotherapy (CRT). In my experience these patients often don't do well. When chromosomal copy number analysis becomes a mainstay tool, I think that we'll see why ... Now this looks weird. It's a video of a gastroscopy, starting just after intubation ... WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSIS?

■ Achalasia

To be specific achalasia type I !

■ Large hiatus hernia

Almost difficult to tell which is oesophagus and what is stomach!

■ Reflux oesophagitis

There is reflux but no oesophagitis

■ Barrett's oesophagus

Oesophagus looks odd but is lined with squamous mucosa

■ Squamous dysplasia

The squamous mucosa is hyperkeratotic but not dysplastic

explanation

This is a patient with end-stage achalasia and a huge, 'sigmoid' oesophagus. OK, the GOJ doesn't look tight but naturally this is because the patient has in the past undergone a myotomy and fundoplication. Patients with 'Type I achalasia' presents with more severe oesophageal dilatation and less spasm-induced pain than in type II and type III achalasia. The silly question for the endoscopist was; 'is there anything we can do to improve swallowing'? Of course, a more important question for the endoscopist was: 'is there any sign of cancer in the distal oesophagus?' After all, both SCC and adenocarcinoma may develop with a frequency of about 1:700 patient/years. Which is about half as common as cancer developing in Barrett's. The GOJ looks a little plump and odd but biopsies did not reveal any neoplasia. Presumably the appearance was due to the previous fundoplication. By the way, the classification of achalasia makes no sense to me at all. This is a case of what would be called 'Type I' achalasia, which I suspect is the end stage of Type II achalasia (logically it should then be called 'Type III achalasia' shouldn't it?). The reason for the suggestion is that in 'Type II achalasia', there is still some preservation of the longitudinal muscle contraction and sufficient excitation of the circular muscle to generate intraluminal pressure but with weak forward propulsion. In type III achalasia, there is a 'nutcracker oesophagus' with a spastic gastro-oesophageal sphincter. Then again, perhaps the three subtypes of achalasia are three completely separate conditions? If you want a reminder of achalasia, here is a link to a good article! |

Categories

All

|