|

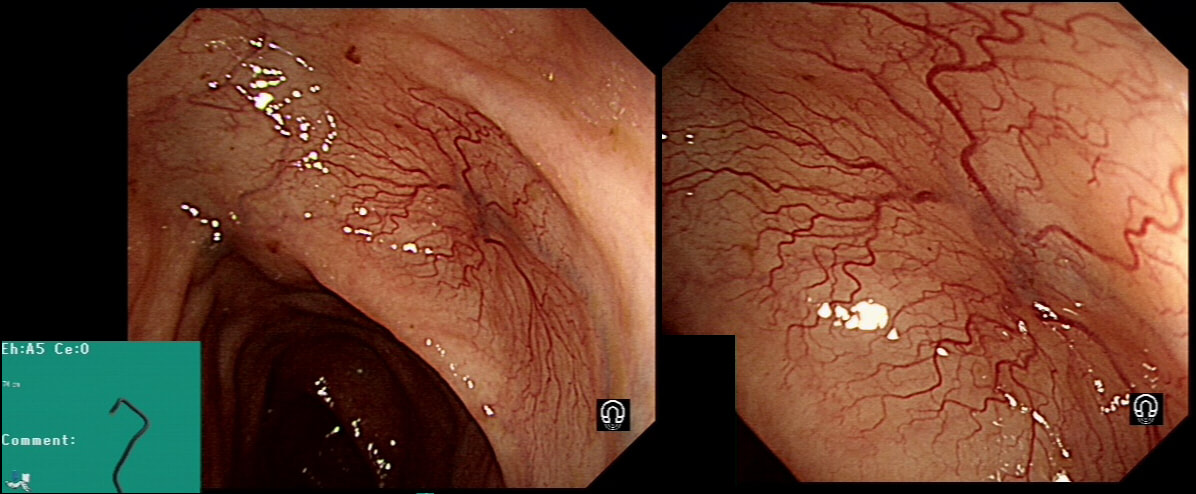

This lesion was found in the transverse colon of a patient with iron deficiency anaemia (IDA).

HOW WILL YOU APPROACH IT WITH APC?

■ Zap the centre first

Absolutely, ablate the central feeding vessel!

■ Start in periphery and work towards centre

Would work but take longer than neccessary

■ In a spoke an wheel pattern starting in the periphery

Would also work but would take longer

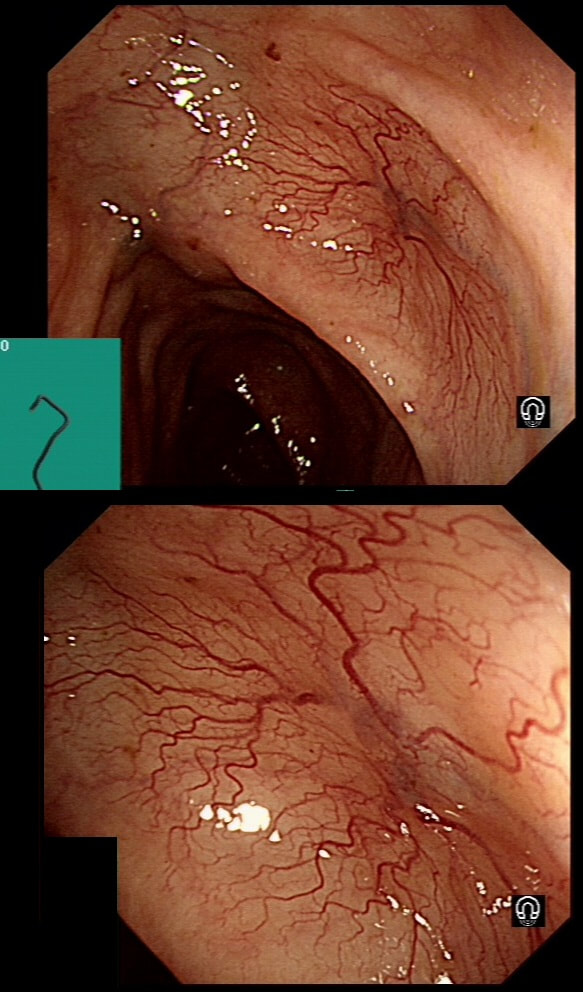

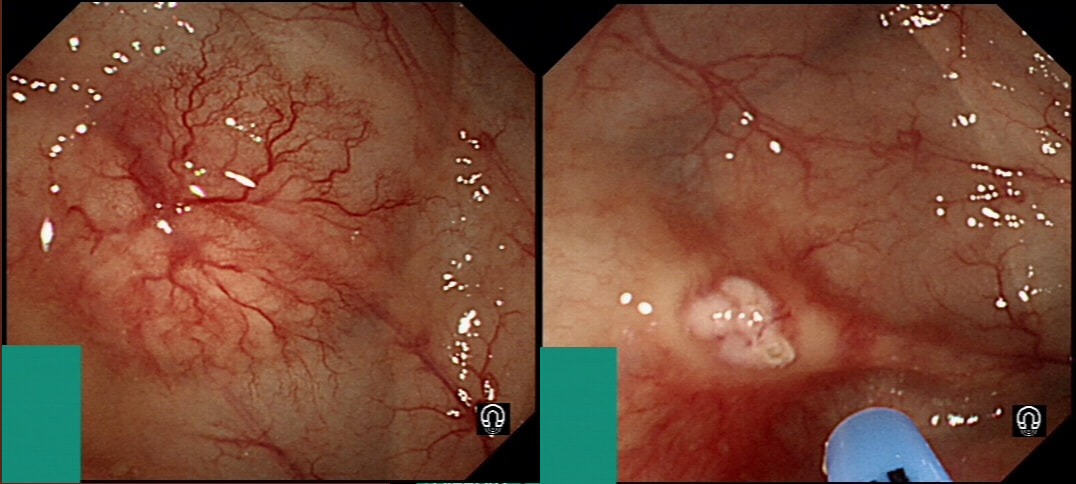

This patient is on a surveillance programme due to alcoholic liver disease but has never had a bleed. He is maintained on a non-cardioselective β blocker. WHEN WOULD YOU RECOMMEND THE NEXT SURVEILLANCE EXAMINATION?

■ None, this patient should be offered banding

Correct, if you decide that there are 'red signs' or the varices are grade II or III

■ In 12 months time

Correct, if you decide that there are no 'red signs' and that the varices are grade I

■ In 2-3 years time

Would only be correct if there are no varices at all!

explanation

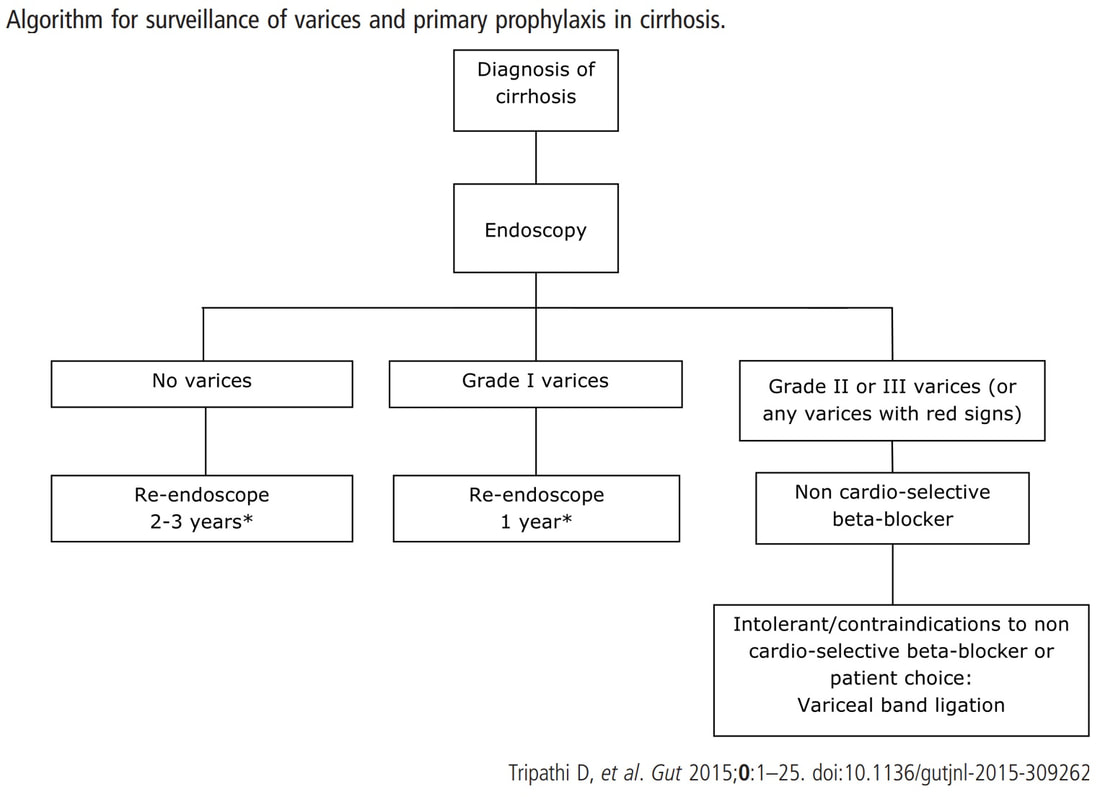

I must admit that I don't like the current surveillance guidelines for patients with portal hypertension. This is a good example why! Although the LFT's had remained stable and the patient had remained abstinent, you could argue that there are 'red signs'. Of course, the presence of 'red signs' predicts progression of varices [J Hepatol 2003;38:266–72] and because the patient is already on a β-blocker, band ligation should now be started. The truth is that 'red signs' are common and have a poor agreement value between endoscopists.

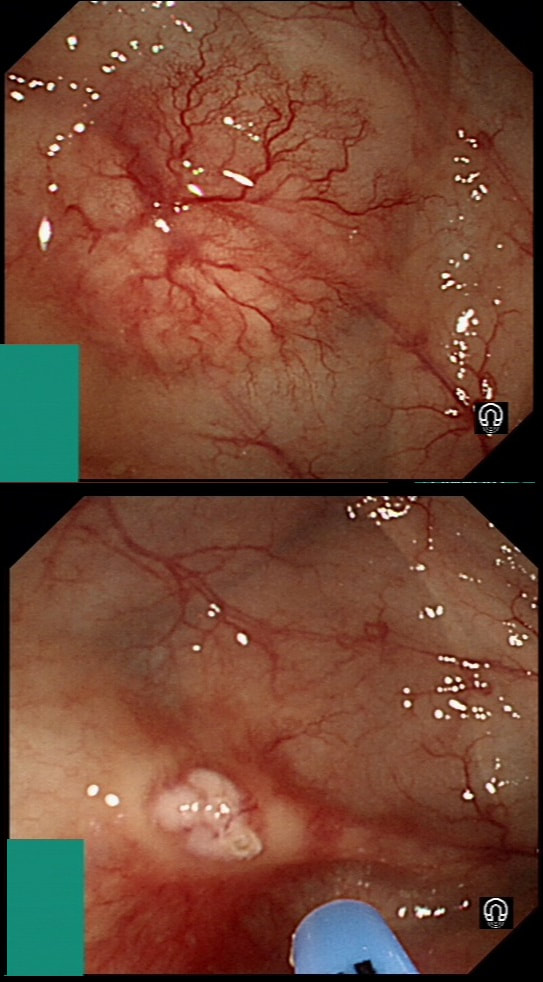

If you decide that there are no 'red signs', and that the varices are grade I only (which depends on the degree of inflation of the oesophagus), the recommendation is to offer surveillance in 1 year. Finally, if you decide that the varices are now grade II (or III), variceal band ligation would be the logical next step. Thus, you can make an subjective argument for any of the above three treatment options. Of course, what you decide will be judged in hindsight. If you decide that these are not red signs and the patient re-presents with a bleed in 6 months time, you could be open to criticism for missing signs of progressive liver disease. Surely, in the modern era of FibroScans, it's possible to predict progression of portal hypertension non-invasively!!! Five years ago, the BAVENO VI workshop only mentioned in passing, that surveillance endoscopies may be avoided in patients with elastography values <20 kPa and a platelet counts >150,000 as these patients are at low risk of progression. Similarly increasing size of the spleen is another warning sign and could be looked for when these patients attend for screening for HCC's. The American guidelines suggest that there is no need to offer patients with untreated viral cirrhosis a screening endoscopy to search for varices IF elastography is <20 kPa and the platelets are >150. They concede that annual elastography and platelet counts may be less predictive in other causes of cirrhosis. However, the American guidelines advice continued surveillance if varices have been found in the past, particularly if liver injury is ongoing. The next Baveno conference in October 2021 will hopefully recommend non-invasive monitoring rather than endoscopy. It would be cheaper, less arduous for patients and offer less subjective findings! The now rather dated BSG guidelines are summarised in the graph below. This video clip requires no introduction. No other abnormality was found. WHERE IS THE LIKELY SITE OF THE PROBLEM?

■ in the portal vein

Then you would expect BOTH oesophageal and fundal varices!

■ In the hepatic vein

In Budd-Chiary, there are no varices!

■ In the splenic vein

Isolated splenic vein varices - absolutely correct!

explanation

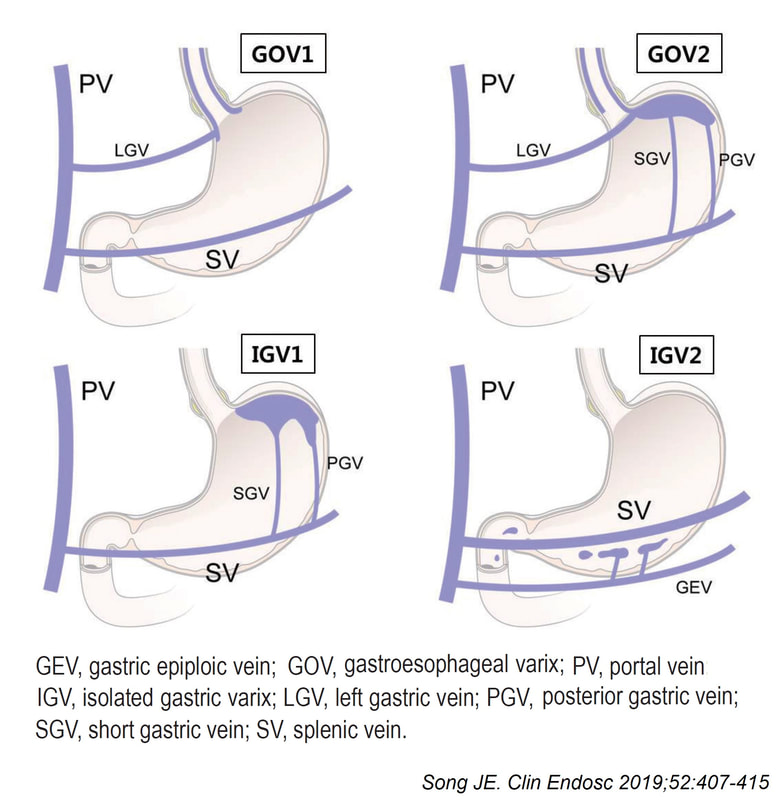

Quoting the 'Sarin Classification' of gastric varices, this is a case of an 'isolated fundal varix' (IGV1). In this case the underlying cause was splenic vein thrombosis following an admission for acute on chronic pancreatitis. The precise distribution of the varices helps you to pinpoint the location of the thrombus. The infographic below from Song et.al is brilliant:

Briefly, 1) oesophageal varices with or without fundal varices points to portal vein thrombosis 2) fundal varices ALONE points to splenic vein thrombosis 3) antral and/or duodenal varices points to a thrombus in the gastro-epiploic vein Brilliant !

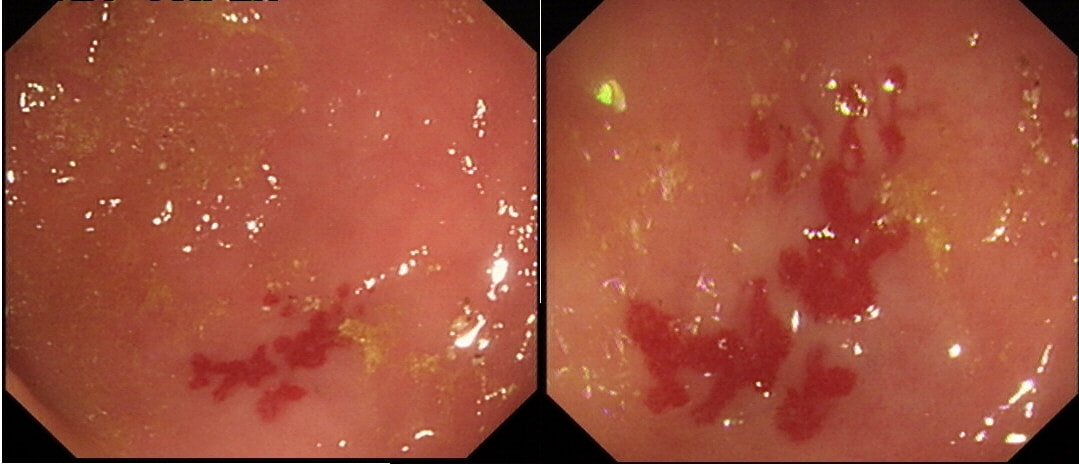

This 70 year old patient with known ischaemic heart disease presents with sudden onset bloody diarrhoea. He undergoes a flexible sigmoidoscopy the following morning and this is what the sigmoid colon looks like. With support and conservative measures symptoms subside and the patient is discharged a week later. However, a week later the patient presents again. Now with hypotension, abdominal distention, fever and a raised white count. An abdominal X-ray is done on admission (below).

WHAT IS THE LIKELY DIAGNOSIS?

■ Colonic stricture

Too soon for this!

■ Another attack of ischaemic colitis

Unfortunately, yes!

■ Pseudomembranous colitis

He didn't actually receive any antibiotics last admission

■ Crohn's disease

Unlikely !

explanation

There is little mystery that the first presentation was due to ischaemic colitis. The second presentation is more tricky. He actually presented with an ileus and pain this time. Actually, the patient had been on aspirin but this had been stopped at the previous admission. This was clearly a mistake as the second presentation turned out also to be due to ischaemic colitis. This time the ischaemic colitis was more severe but he did recover in the end.

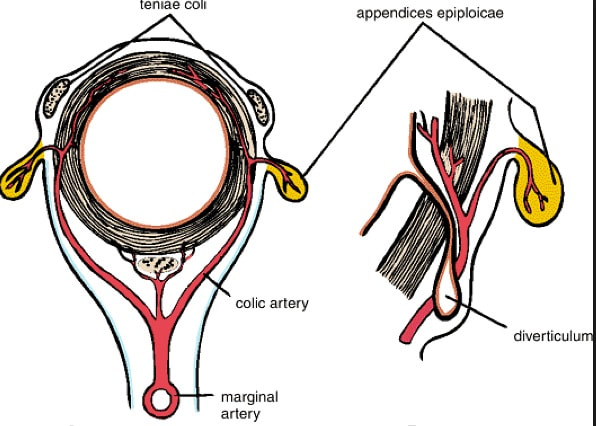

After ischaemic colitis about 10% of patients develop and ischaemic stricture but it takes longer than a single week to develop. The hallmark of an ischaemic colitis are areas of longitudinal ulceration, on the anti-mesenteric border (90° to any diverticulum) where the blood flow is the slowest. Of course, endoscopically its difficult to tell where the omental reflection is situated. However, the ulceration will run along one aspect of the colonic circumference. Of course in the epicentre of the ischaemic (typically around the splenic flexure), the ulceration may well be circumferential. Ischaemic colitis is surprisingly easy to confirm histologically as the pathologists look for crypt withering and fibrosis. By the way, if the mucosa looks dusky and there is no bleeding on taking samples, the likelihood is that the colon is turning gangrenous, associated with a >50% mortality rate.

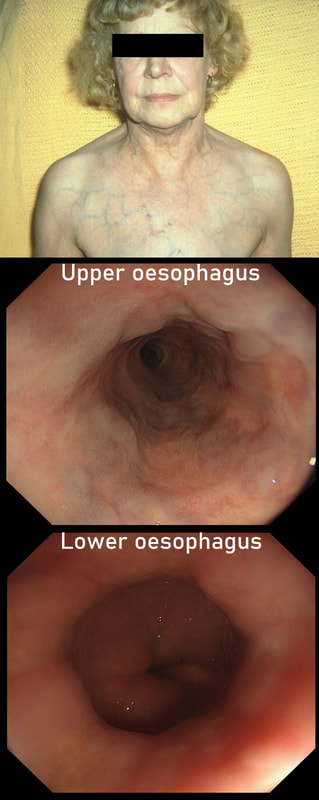

This lady is undergoing a gastroscopy

WHAT IS THE LIKELY DIAGNOSIS?

■ Cirrhosis and portal hypertension

Look again!

■ Splenic vein thrombosis

Gives you gastric varices!

■ Hepatic vein thrombosis

Pts present with ascites and normal LFT's!

■ SVC obstruction

Too easy perhaps?

explanation

‘Downhill oesophageal varices’ are associated with superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction or obstruction or as in this particular endoscopic case, a clot in the right brachiocephalic, subclavian and axillary veins. I thought that just showing the oesophagus would make the question too difficult and therefore added the photo of a patient with SVC obstruction. Perhaps this made it too easy ☺!

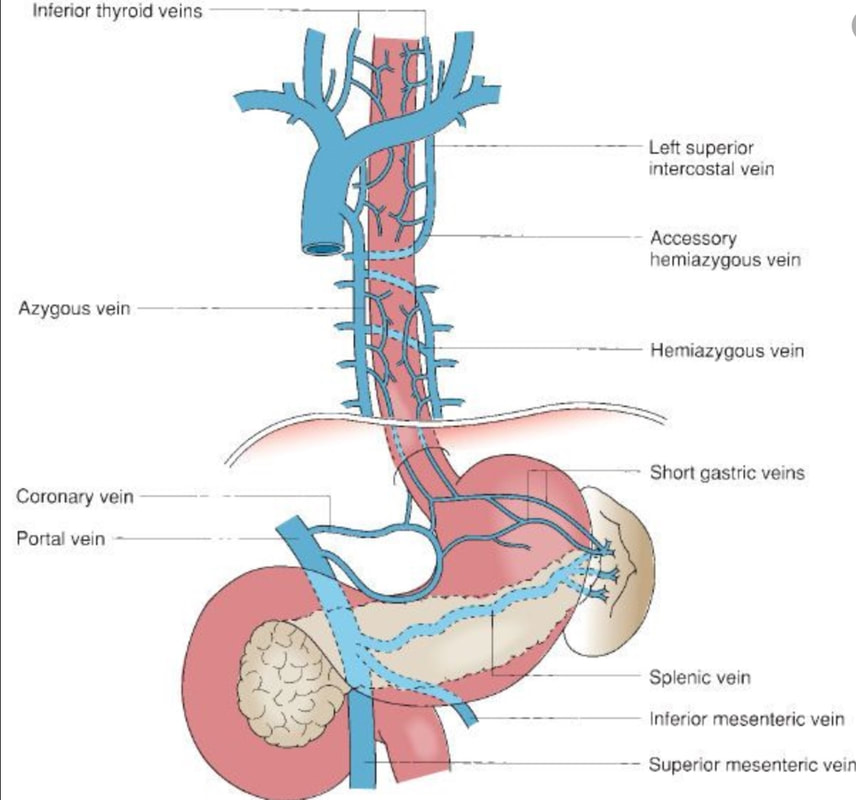

Venous drainage of the oesophagus is through the azygos and hemiazygos veins (see below). When there is thrombus, retrograde flow pushes blood towards the heart via collateral channels. If the obstruction is above the level of the azygous vein, varices develop in the upper oesophagus. However, if the clot is below, or involves the azygous vein, varices will form along the entire oesophagus. Bleeding is rare as varices in the proximal oesophagus are situated deeper within the submucosa than distal varices. However, if you are asked to deal with bleeding, you need to place bands at the proximal end of the varix. Sclerotherapy is contraindicated in the high oesophagus because of the risk of spinal cord infarction and vertebral infarction. Glue injection should also be avoided as there has been a case report of a massive PE.

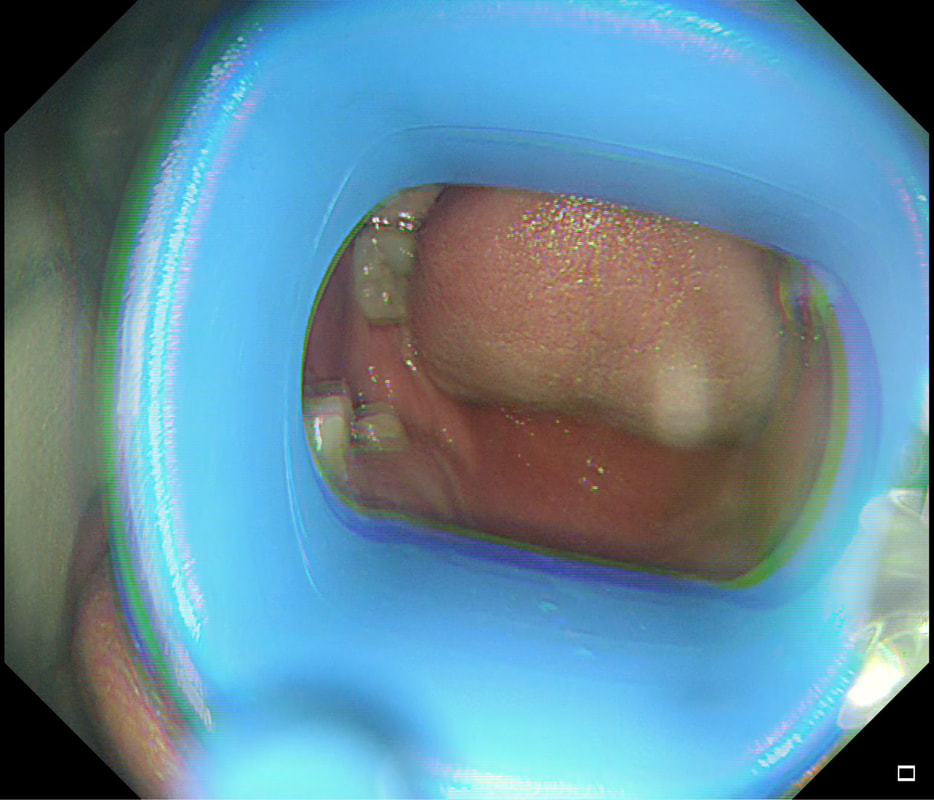

This lesion was found in the transverse colon of a patient with a change in bowel habit

HOW WILL YOU MANAGE THIS?

■ I will ignore it

Brilliant, so would I !!!

■ Apply APC in the centre

Yes but only if patient has an IDA !

■ Apply APC from the periphery and working inwards

Advocated by some but life's too short!

■ Inject saline below and then apply APC

Overkill I think ...

■ Apply a clip to the centre

Doesn't work!

explanation

Angioectasia (formerly called 'angiodysplasia but of course these are not 'dysplastic'/ pre-malignant) are an acquired vascular malformation associated with advancing age, aortic stenosis, Von Willebrand Disease and chronic kidney disease. If a patient asks me, I usually put it more diplomatically as 'these come with maturity'. Seems kinder!

They are supposedly a little more common on the right than the left side. IF the patient is anaemic, APC is the treatment of choice. I have tried clips but they don't work. Be careful though as APC has been linked with delayed perforation in up to 1% of cases [Olmos J A. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1507–16]. I turn the APC down to 30 watts only and set the machine to 'pulsed APC'. Even so, please be sensible and stop after a maximum of a few seconds of heat! Some first raise the lesion with saline but first I don't think that this is necessary unless you are careless with the APC and secondly, I runs the risk of the underlying central, feeding vessel not actually getting ablated. Of course you could also use a 'coagulation grasper' if you are willing to pay €250 for the same outcome. Alternatively, you may consider a 'hot biopsy forceps' but of course these are now 'banned' and could land you in deep trouble if there is problem. Must admit that I use them instead of coagulation graspers because I'm too stingy to pay the €250. The correct answer in this case is probably not to do anything as the patient is not anaemic (and presumably has never been anaemic in the past). Secondly, I would advocate that you apply heat to the centre of the lesion only as those spidery legs will then disappear as in the example below.

By the way, it's not described in literature but there are actually two types of angioectasia. There are the 'spider naevi like' angioectasia as in the case above but angioectasia more commonly appear as red blobs as in the example below. Must admit that I don't know why. Must have something to do with the aetiology ...

A 46 year old lady with autoimmune hepatitis is admitted with jaundice, and deteriorating LFT's. She is started on 40mg of prednisolone but has a small haematemesis a couple of days later. On the morning of her endoscopy, nursing staff has documented that she is confused. However, on arrival to the endoscopy unit she is very drowsy. There are no focal neurological signs and the nurse who has escorted her down from the ward denies that she has been given any sedatives. You review her recent blood results:

Hb 125 WCC 12.9 Plat 85 Bili 250 µmol/l AST 310 iu/l ALP 230 iu/l Albumin 33 g/l Bicarbonate 15 mmol/l Blood gases on air pH 7.29 pCO2 2.9 kPa pO2 16.8 kPa Anion gap 25 WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT?

■ Check the blood sugar

Absolutely but do you expect the level to be high or low???

■ Check the clotting

Hmm, of little relevance to her drowsiness

■ Check her U&E's

Hard to imagine that it will affect your immediate management?

■ Request a CT head

Would this really be your first intervention?

■ Go ahead with the OGD

May or may not be 'correct' but wouldnt' you do something else first?

explanation

This is a difficult question as the initial thought is; "What could possibly precipitate coma in a patient with liver disease?

Of course the answer to that questions is:

However, you may have failed to notice that the coma occurred after starting her on high dose prednisolone and that the patient has a marked metabolic acidosis? Next you need to rule out the possibility of 'steroid induced ketoacidosis' by checking the blood glucose level. Of course, a blood sugar is much quicker than getting a head scan and should be done before even considering going ahead with the OGD. Would I then go ahead with the endoscopy? Hmm, yes IF the patient has more solid evidence of a significant UGI bleed with haemodynamic instability and after resuscitation with insulin and fluids etc. |

Categories

All

|